Preface

About me

I'm the currently most active maintainer of the GraphFrames project and a big enthusiast of Apache Spark and Graph analysis. I'm not affiliated to any company selling GraphFrames or Apache Spark itself and my work on the project is based on a pure enthusiasm and passion to Open Source. I can estimate my knowledge of Apache Spark as medium: I know the API and some details of internal implementation and how Spark works from the top-level of view. But I'm not a contributor of Spark or engineer who is working on Spark internals. I do not have any CS-degree or DS-degree and my knowledge of the Data Science field as well as Graph Data Science are limited to what I read and try. And this post will be as honest as possible, and if I'm not sure in something or don't know something I will tell about it explicitly. No LLM was used to generate the text or any of its parts. However, because English is not my native language, I use DeepL Write from time to time.

About GraphFrames

GraphFrames is an open source extension for the Apache Spark that aims to bring easy to use graph algorithms to the Spark ecosystem. While there are a lot of single-node libraries for graph processing and graph machine learning, they cannot be scaled to billions of nodes and edges. At the same time, there are a lot of specialized solutions for distributed graph processing, but they required a separate infrastructure and are hard to maintain. GraphFrames aims to somewhere in the middle. If you already have a huge graphs, like user-item interactions, financial transactions or identity graphs, but still not ready to heavily invest in the specialized infrastructure, you can re-use existing Spark with GraphFrames. Spark today is a de-facto standard for big-data industry, so with GraphFrames teams can easily add some big-data graph features to their pipelines on top of existing processing. GraphFrames is a pure open-source project, maintained by the group of independent contributors and it is not backed by any vendors as well GraphFrames does not have any kind of paid version or enterprise support.

About Graphs

I will not write again about basic graph concepts and how the graph can be processed in a Map-Reduce ways. You can read about it in my another blog post. For this post it is enough to understand that Graph in GraphFrames is modeled as two relations: edges and vertices. Because code snippets will be in Scala and Spark, some basic knowledge of this two is required.

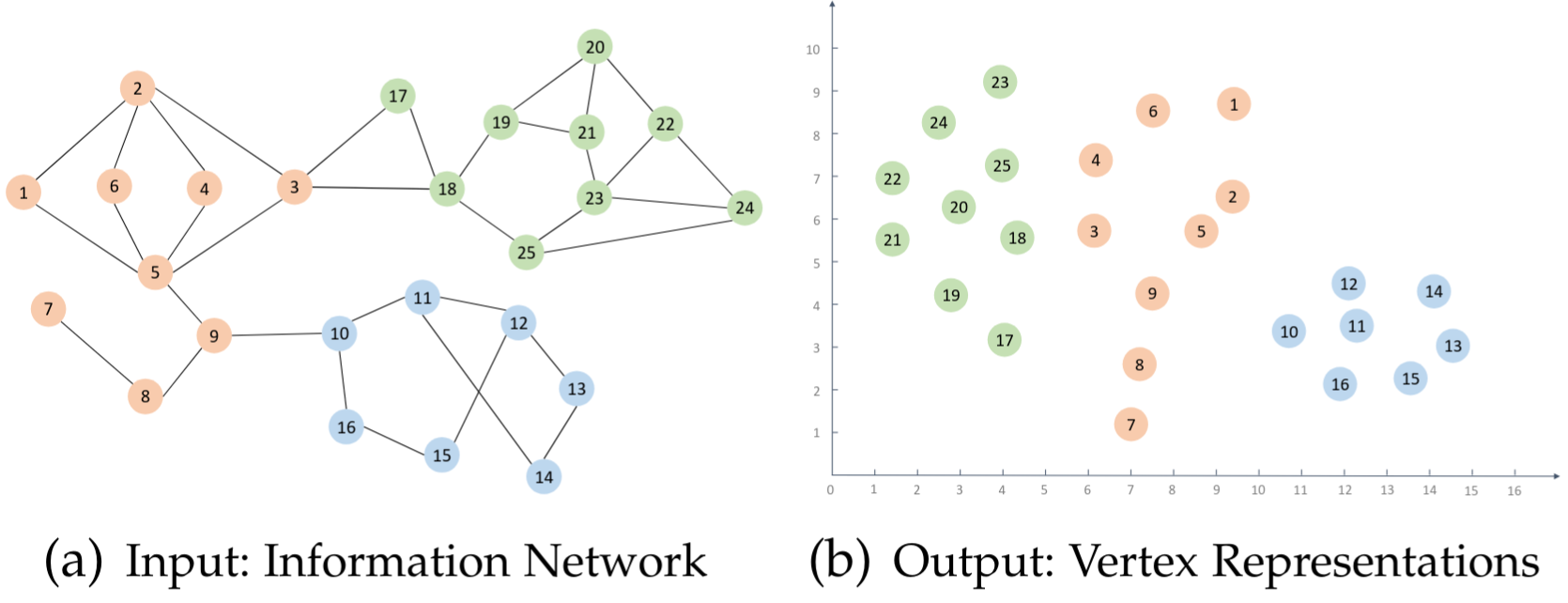

Vertex Representation Learning

Vertex Representation Learning (aka node embeddings) is a task to assign to each vertex of the graph a vector of floating numbers. Such a vector should contain information about neighborhood of the vertex, it's similarity with other vertices, etc. The simplest to understand case is a 2D representations when we map vertices of the graph to 2-dimensional vectors. In this case we can visualize the picture to see how embeddings are different for vertices that are part of different clusters in the input graph.

Usage of node embeddings

An obvious question is why do we even need this embeddings? So, let's briefly view what can we do with embeddings.

- Node classification. One of the most-common case. We have some labels, like who is who in our social network. Who is fraud-account or bot, who is not. Or, for example, if we have an electricity grid network, what is the most risky node? And a lot of other examples;

- Link Prediction. If we assume that our graph is not "complete" and there are some additional connections we are not aware about, we can try to predict the probability of edges between nodes. It naturally leads us to the RecSys story. If we are "building Netflix" and want to recommend movies to people, we can represent the problem as a bipartite graph where user is connected to the movie if they liked / watched it. And our goal is to recommend to the user a new movie or to predict edges in this bipartite graph in other words;

- Graph Clustering. When we have numeric representation of vertices, we can apply any of known clustering algorithm on top of our embeddings to get clusters;

- De-duplication and similarity. One of the common graph problems. We have a lot of nodes and we are knowing that some of them are actually the same entity. Having compact numeric representation of vertices allows us to use nearest neighbors and similarity search to identify them.

And a lot of other problems that can be solved with numeric representation of vertices.

Alternative approaches to graph embeddings

This post is about Random Walks based embeddings, but before we go further I will try to briefly cover alternative ways of generating vertex representations.

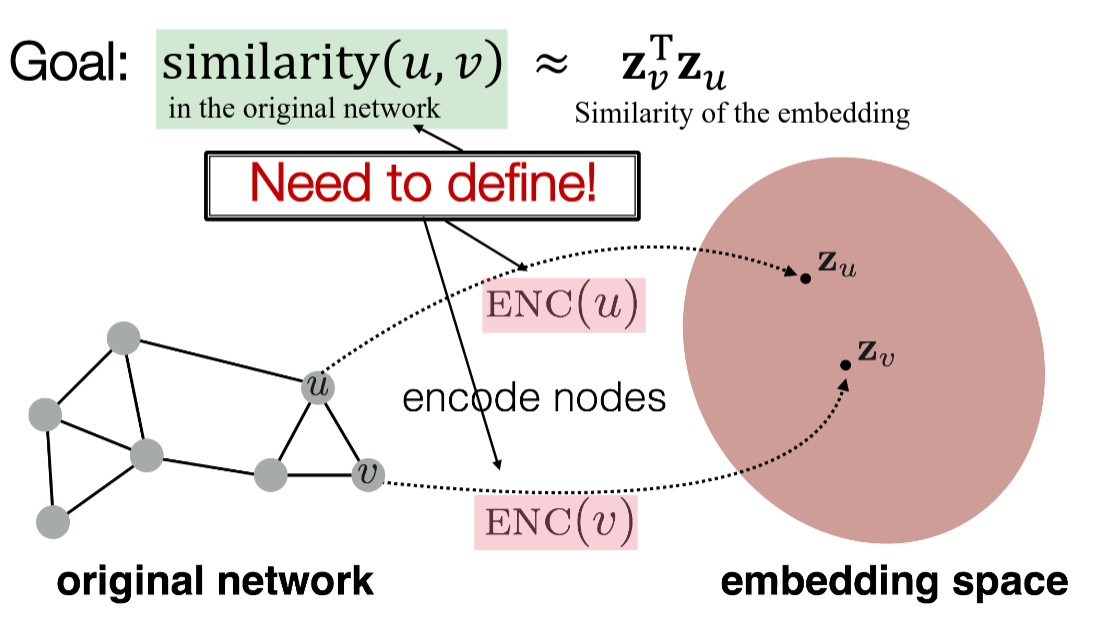

Encoder-decoder approach

If we can define anyhow the similarity between vertices of the graph, we can use the well known encoder-decoder approach.

In this case, we can sample pairs of very similar vertices and sample pairs of not similar vertices (so called negative-sampling) and try to maximize something like a cosine distance in embeddings space between vertex representations. It may even work without negative sampling. The main problem here is to define a similarity metric. What should it be? Jaccard score? Links? The same cluster?

While the idea looks interesting, I don't see a lot of real-world applications of it.

Decomposition of adjacency matrix

Each graph can be represented as a matrix actually. Let's imagine we have the graph with vertices 0, 1, 2, 3, 4. And we have the following edges: 1 -> 2, 1 -> 3, 2 -> 4, 3 -> 0, 0 -> 4. We can build a so-called adjacency matrix:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In this matrix element \( e_{ij}\) is equal to one if there is an edge between vertices \(i\) and \(j\) and zero otherwise.

While an adjacency matrix is already a representation of vertices by vectors, the size of such a matrix is growing very fast as well as adding new vertex will change this matrix. The second problem cannot be resolved easily, but the size can be addressed by matrix decomposition approach. The most used is Singular Value Decomposition (SVD). I won't stopping on it, because the problem of changing this matrix if a vertex is added cannot be resolved anyway. As well as SVD is very expensive from the computation point of view and such an approach barely will work on real world graphs with hundreds of millions of vertices.

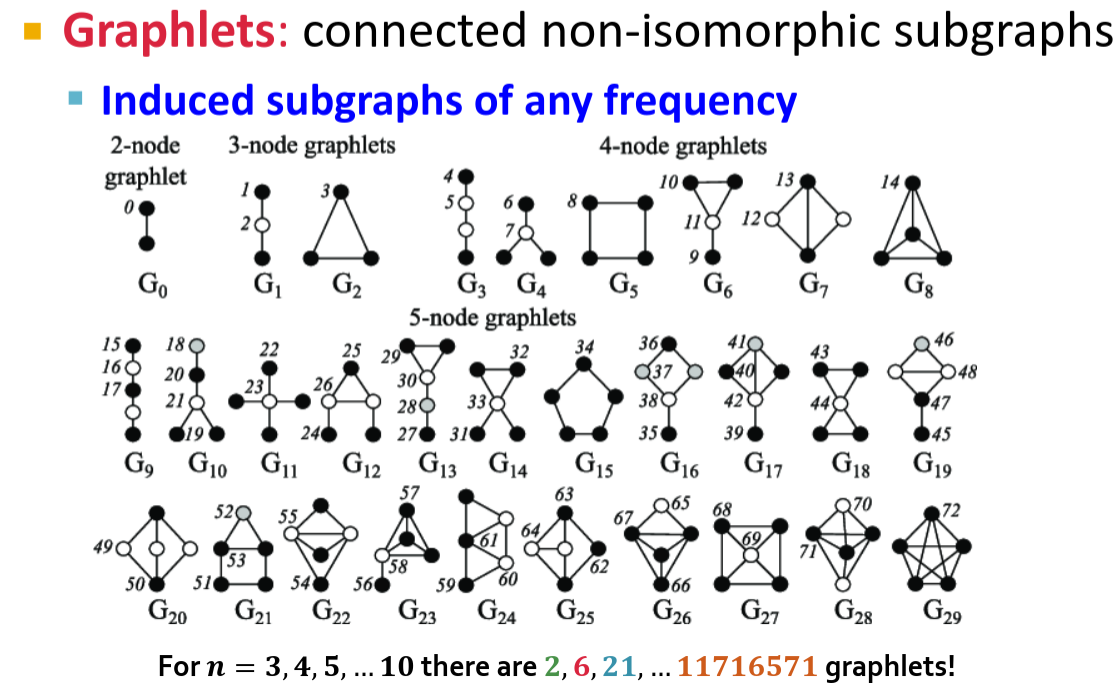

Graphlet Degree Vectors

Graphlets is a topic, but long story short, we can consider subgraphs of small size and there are not to many of them actually.

If we enumerate all the graphlets as index and use an amount of graphlets of each type as a values, we can construct a vector. This vector is called a Graphlet Degree Vector (GDV) and is a kind of vertex representation. While the are efficient algorithms to (approximately) enumerate graphlets, they are not easy to implement and GDV itself encodes very specific information. I have a plan to implement distributed GDV in GraphFrames one day, but at the moment the project needs a simpler and more generic approach.

GNN and GraphSAGE

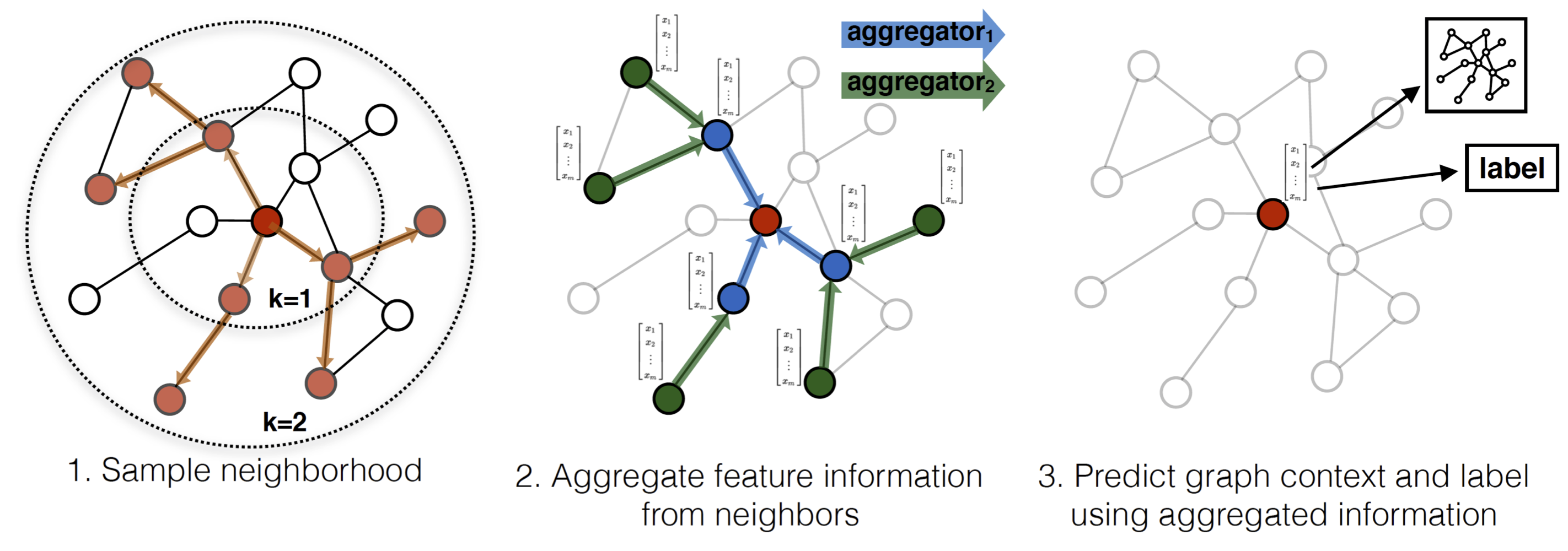

The most advanced methods of vertex representation learning is Graph Neural Networks (GNN) and Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (GCNN). The idea is quite a simple (but only idea, implementation, and tuning is very hard). We can take information from neighborhood of each vertex and apply a convolution operation. Each level of convolution (1-st neighbors, 2-d neighbors, etc.) have each own matrix of numerical weights (that should be learned) and we do matrix multiplication to compute the final representation.

While it is the most powerful method, it is not very easy to implement, very hard to tune and even more hard to scale up to graphs for that GraphFrames is supposed to be used. I'm still going to look into it after implementing basic embeddings, but it is definitely not the first step.

GNN and random weights

There is one more topic related to GNNs that we actually may even skip the whole learning process and use random weights. I will return to it at the end of the post, in the section about what's next.

Random Walks

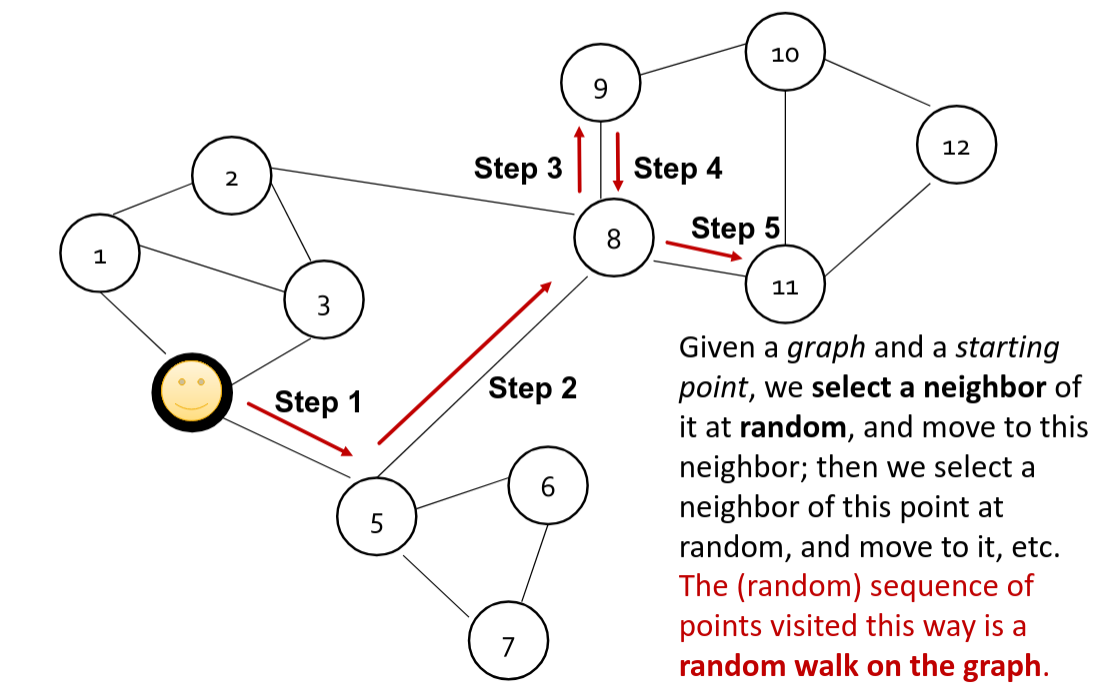

What is the Random Walks algorithm? Actually it is just a way to generate sequences of vertices. If we imagine an agent who starts from a vertex and start randomly visiting other vertices, the path of such an agent is called a "Random Walk".

Modifications of Random Walks

First-order Random Walks

The simplest possible algorithm is the so-called 1st order Random Walks. In this case we just simply choose the next vertex to visit based on the uniform distribution from all the neighbors of currently visited one. It is very easy to implement and it is scalable. It is perfectly fit into the distributed graph processing. At first step we can collect on each vertex all the possible candidates for the next destination of the walk. After that we may run N independent walkers starting from different vertices. This create a dataset of walks, that on the first step contain only currently visiting (starting) vertex. On each step, we join to the dataset of walks the dataset of possible neighbors using the condition that currently visiting vertex ID should be equal to the ID from candidates dataset. Now we have all the candidates for the currently visiting node and can choose next, append the current to the walk and set the chosen as current.

Let's use DuckDB for simple step-by step explanation.

D CREATE TABLE edges AS SELECT * FROM

(VALUES (1, 2), (1, 3), (2, 3), (2, 4), (3, 9), (6, 7), (6, 8))

edges(src, dst);Now we should create from edges all the possible node candidates:

D CREATE TABLE candidates AS SELECT src, list(dst) AS candidates FROM edges GROUP BY src;

D SELECT * FROM candidates;

┌───────┬────────────┐

│ src │ candidates │

│ int32 │ int32[] │

├───────┼────────────┤

│ 1 │ [2, 3] │

│ 2 │ [3, 4] │

│ 3 │ [9] │

│ 6 │ [7, 8] │

└───────┴────────────┘An interesting question is what should we do if our agent come to the vertex, that does not have outgoing edges? And a common answer is "do restart" or just start from the beginning in other words. Let's start walkers from vertices 1, 2, 3 and 6 that only has outgoing edges.

D CREATE TABLE walks AS

SELECT DISTINCT [] AS walk,

src AS current_vertex FROM edges WHERE src IN (1, 2, 3, 6);

D SELECT * FROM walks;

┌─────────┬────────────────┐

│ walk │ current_vertex │

│ int32[] │ int32 │

├─────────┼────────────────┤

│ [] │ 1 │

│ [] │ 2 │

│ [] │ 6 │

│ [] │ 3 │

└─────────┴────────────────┘Now we need to do a join of candidates and walks based on the currently visited vertex. After that we can sample next candidate, mark it as currently visited and append an old "current" vertex to walks. There is no randn function in DuckDB (or maybe I just failed to find it), so let's do some strange magic.

D CREATE TABLE walks2

AS SELECT

list_append(walk, current_vertex) AS walks,

candidates[cast(ceil(random() * len(candidates)) AS int)] AS current_vertex

FROM walks JOIN candidates ON src = current_vertex;

D SELECT * FROM walks2;

┌─────────┬────────────────┐

│ walks │ current_vertex │

│ int32[] │ int32 │

├─────────┼────────────────┤

│ [1] │ 2 │

│ [2] │ 3 │

│ [3] │ 9 │

│ [6] │ 8 │

└─────────┴────────────────┘Now we face exactly this case: some of current vertices does not have outgoing edges and we should do "restart":

D CREATE TABLE walks3

AS SELECT list_append(walks, current_vertex) AS walks,

coalesce(

candidates[cast(ceil(random() * len(candidates)) AS int)],

walks[1]) AS current_vertex

FROM walks2 LEFT JOIN candidates ON src = current_vertex;

D SELECT * FROM walks3;

┌─────────┬────────────────┐

│ walks │ current_vertex │

│ int32[] │ int32 │

├─────────┼────────────────┤

│ [1, 2] │ 3 │

│ [2, 3] │ 9 │

│ [3, 9] │ 3 │

│ [6, 8] │ 6 │

└─────────┴────────────────┘And we can continue generating walks in such a way:

D CREATE TABLE walks3

AS SELECT list_append(walks, current_vertex) AS walks,

coalesce(

candidates[cast(ceil(random() * len(candidates)) AS int)],

walks[1]) AS current_vertex

FROM walks2 LEFT JOIN candidates ON src = current_vertex;

D SELECT * FROM walks4;

┌───────────┬────────────────┐

│ walks │ current_vertex │

│ int32[] │ int32 │

├───────────┼────────────────┤

│ [1, 2, 3] │ 9 │

│ [3, 9, 3] │ 9 │

│ [6, 8, 6] │ 8 │

│ [2, 3, 9] │ 2 │

└───────────┴────────────────┘At the end of such an iterations we will have sequences of "visited" vertices or multiple random walks.

Second-order Random Walks

In the previous toy example we did not use anyhow the history of visited nodes. That is why such an approach is named first-order Random Walk. But there are alternative ways. The simplest example of 2d order Random Walk is the so called no-backtracking algorithm. It is the same simple random walk with one additional condition: we cannot go back to the vertex that was the last visited one. Even such a simple update allows walkers to avoid visiting the same vertices multiple times and explore more deep neighborhood instead.

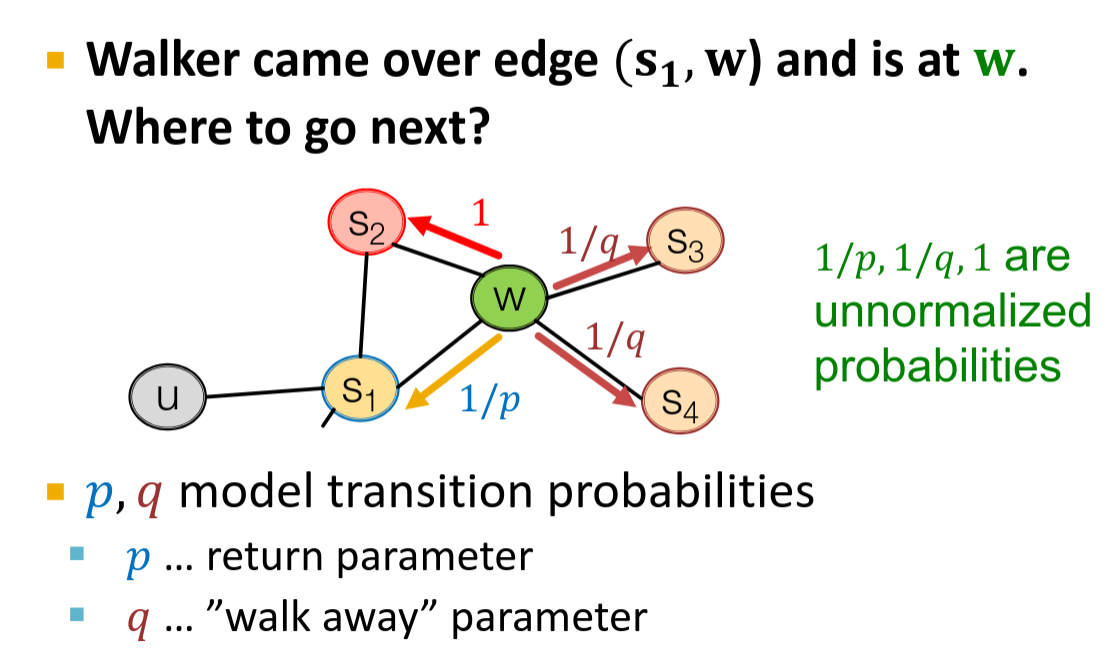

The more advanced example is an implementation of Random Walks behind the Node2Vec algorithm (Grover, Aditya, and Jure Leskovec. "node2vec: Scalable feature learning for networks." Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining. 2016.)

In node2vec there are two hyper parameters that allows balancing between Depth-First search and Breadth-First search. In other words, to bias walkers to explore close neighborhood or to bias walkers to explore deep neighborhood of the starting vertex.

At the same time there is a problem with 2d order Random Walks in distributed graph processing. Remember how we collected candidates in DuckDB example? For 2d order algorithm we should collect neighbors of neighbors… If we imagine a real world graph with billions of nodes that may have a degree of hundred thousands, collecting 2-hop neighbors will easily lead to the memory blow up. At the same time, the simple 2d order algorithms like no-backtracking (or no 2-back tracking, etc.) can be modified to work in distributed scenarios.

Random Walks with restart

We already mentioned the case when our walker is stuck in the vertex with non outgoing edges. In this case we were forcing our walkers to do restart or start from the beginning in other words. But why not to add a small probability to do restart on each step? This leads us to the Random Walk with restart algorithm that show better results compared to a simple Random Walks approach. For example, the well known PageRank algorithm is actually a Random Walks with restart.

A typical approach is to set probability of restart to a number \(\sim\leq 0.2\). I would like also to mention, that from my understanding, Random Walk with restart is not compatible with any kind of the 2d order Random Walk techniques. As I can understand, they are relying on different assumptions and mixing them will just break both. But I can be wrong here.

Weighted Random Walks

Another obvious modification of Random Walk algorithm is to use edge weights (or node attributes) on the stage of sampling the next candidate. For example, instead of doing a fully random sampling, we can do sampling based on weights. We can normalize weights and consider them as probabilities. This is a good addition that can be combined with any of the mentioned above modifications.

Temporal Random Walks

A separate story is the so-called Temporal Random Walk approach. The only modification that we need to do is to ensure that vertices in sequence are following the time. On the stage of selecting the next candidate, we are choosing it by the condition that timestamp of the corresponding edge is greater (or equal) to the timestamp of the previous edge.

Implementation with GraphFrames and Spark

Now it's time to implement it with Spark and GraphFrames. Graph in GraphFrames is modeled by two Spark's DataFrame objects, one for edges, one for vertices. As well as because it is Spark we should keep in mind the following limitations:

- Avoiding shuffling of long arrays and generating heavy rows. In our DuckDB toy example, each iteration is join that on Spark and GraphFrames will lead to shuffle;

- Distribute the work equally across the cluster. If one vertex has 10 possible candidates for the next walk, but another has 1000 it will create a skew;

- Avoid long chaining transformations without writing or checkpointing: growing lineage and long plan optimization time is a curse of Spark;

After thinking a lot, I stopped with the following concept.

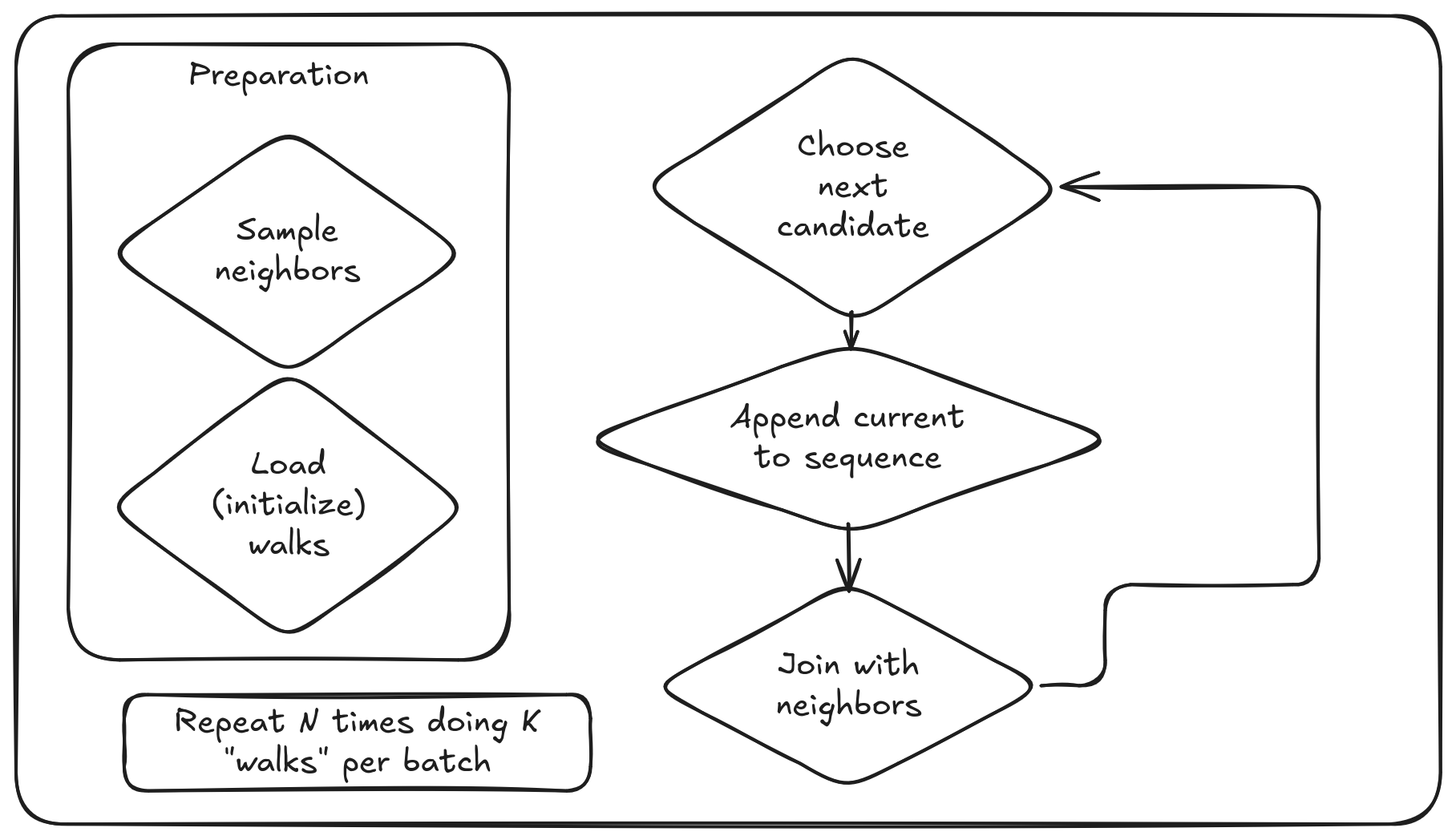

The idea is to split algorithm to batches and limit the sequence length that is kept in memory. On each batch we read the "end" of the walk from the previous batch (or initialize a new if it is the first iteration). For 1st order Random Walks it is enough to read only the currently visiting vertex, for the no-backtracking we need also a previously visited one, etc.

Inside each batch we are sampling at most K neighbors per vertex that are possible candidates for the next walk. Sampling is very important here, otherwise on power-law real-world graphs we can easily face huge skew due to fact that 1% of vertices can handle half of the whole edges of the graph.

When we sampled neighbors and have a prepared walks, we can do joins in the same way like in the above DuckDB toy example.

Sampling at scale

The first problem is how to sample neighbors effectively. If we have a directed graph we may want to use edge directions during walks generation. So, we can take edges, group by src, collect dst, shuffle and take first K. Unfortunately it is very inefficient as well as it creates a huge skew in map-reduce operations. The better solution would be to use a reservoir sampling algorithm, that is specifically designed for such a case. The idea of algorithm is very simple. If we have a stream of elements and we want to sample K of them uniformly, we are creating a reservoir, or array of the size K. Next we fill it by first K elements of the stream. For each next element, let's say it will be i-th processed element, we are generating a random number from 0 to i. This random number is j_{i}. If j_{i} \leq K, that we are replacing the j-th element of the reservoir by the i-th element of the stream. For proof of the uniform distribution of the resulted sample I will point you to the Wikipedia.

In Spark it is slightly more complicated, because our aggregation is distributed, so we need not only implement sampling, but also implement merging of two reservoirs.

Let's start from the required imports and definition of the Scala case class for the reservoir itself. From the definition of algorithm it is clear that we should store only current sample plus total amount of visited elements to be able to generate randoms.

package org.apache.spark.sql.graphframes.expressions

import org.apache.spark.sql.Encoder

import org.apache.spark.sql.Encoders

import org.apache.spark.sql.catalyst.encoders.ExpressionEncoder

import org.apache.spark.sql.expressions.Aggregator

import scala.reflect.runtime.universe.TypeTag

import collection.mutable.ArrayBuffer

case class Reservoir[T](seq: ArrayBuffer[T], elements: Int) extends SerializableIt is important to mention, that such a class should inherit the Serializable!

Now we can write the aggregation routine itself. It should inherit Aggregator. It also should define the type of input elements, in our case it is vertex type, type of the state that is Reservoir and an output type that in our case is Seq. TypeTag is required by Spark to correctly ensure serialization. Or at least that I how I see it. Maybe it is not needed here, I'm not 100% sure to be honest. The size argument here is the mentioned above K or just an amount of samples we want to have.

case class ReservoirSamplingAgg[T: TypeTag](size: Int)

extends Aggregator[T, Reservoir[T], Seq[T]]

with Serializable {}zero method is required by Spark to initialize empty aggregators. In our case it is trivial. We create an empty mutable ArrayBuffer and initialize an amount of processed elements by zero.

override def zero: Reservoir[T] = Reservoir[T](ArrayBuffer.empty, 0)Now we need to implement a reduce step that takes a next element and try to add it to reservoir.

override def reduce(b: Reservoir[T], a: T): Reservoir[T] = {

if (b.seq.size < size) {

Reservoir(b.seq += a, b.elements + 1)

} else {

val j = java.util.concurrent.ThreadLocalRandom.current().nextInt(b.elements + 1)

if (j < size) {

b.seq(j) = a

}

Reservoir(b.seq, b.elements + 1)

}

}Beside the fact that I'm not sure it is safe to use ThreadLocalRandom inside Spark's aggregation functions it is a straight-forward implementation of the basic Reservoir Sampling. My only concern is what happens if Spark needs to recompute failing stages? May the ThreadLocalRandom breaks the execution flow and fault tolerance guarantees of Apache Spark? I do not know to be honest. Answer to the question requires much deeper understanding of Spark that I have. I tried to ask in the Spark mailing list, but unfortunately I got zero answers. So, as is.

The next is merge of two partially complete reservoirs. That is more tricky and I split it to three separate cases:

- both reservoirs are already collected

Kelements - one of the reservoirs is full, the second is not

- both reservoirs are not full

In the case of two full reservoirs we need to sample randomly from both and return the new reservoir and a sum of processed elements by both. To be honest, I'm not sure do I really need to clone buffers or not. But it is cheap O(K) and I decided to do it to avoid tricky race conditions debugging.

private def mergeFull(left: Reservoir[T], right: Reservoir[T]): Reservoir[T] = {

val total_cnt = left.elements + right.elements

val rng = java.util.concurrent.ThreadLocalRandom.current()

val pLeft = left.elements.toDouble / total_cnt.toDouble

var newSeq = ArrayBuffer.empty[T]

val leftCloned = left.seq.clone()

val rightCloned = right.seq.clone()

for (_ <- (1 to size)) {

if (rng.nextDouble() <= pLeft) {

newSeq = newSeq += leftCloned.remove(rng.nextInt(leftCloned.size))

} else {

newSeq = newSeq += rightCloned.remove(rng.nextInt(rightCloned.size))

}

}

Reservoir(newSeq, total_cnt)

}Now it's time for the case when both reservoirs are not full yet. In this case we can take K first elements and perform sampling for the rest.

private def mergeTwoPartial(left: Reservoir[T], right: Reservoir[T]): Reservoir[T] = {

val total_cnt = left.elements + right.elements

val rng = java.util.concurrent.ThreadLocalRandom.current()

if (total_cnt <= size) {

Reservoir(left.seq ++ right.seq, total_cnt)

} else {

val currElements = left.seq ++ right.seq.slice(0, size - left.elements)

var currSize = size + 1

for (i <- ((size - left.elements) to right.elements)) {

val j = rng.nextInt(currSize)

if (j < size) {

currElements(j) = right.seq(i)

}

currSize += 1

}

Reservoir(currElements, currSize)

}

}And finally the case when one reservoir is full and another is partial. In that case we are sampling randomly from both.

private def mergePartialRight(left: Reservoir[T], right: Reservoir[T]): Reservoir[T] = {

val total_cnt = left.elements + right.elements

val pLeft = left.elements.toDouble / total_cnt.toDouble

val currElements = ArrayBuffer.empty[T]

val rng = java.util.concurrent.ThreadLocalRandom.current()

val clonedLeft = left.seq.clone()

val clonedRight = right.seq.clone()

for (_ <- (1 to size)) {

if ((clonedRight.isEmpty) || (rng.nextDouble() <= pLeft)) {

val idx = rng.nextInt(clonedLeft.size)

currElements += clonedLeft.remove(idx)

} else {

val idx = rng.nextInt(clonedRight.size)

currElements += clonedRight.remove(idx)

}

}

Reservoir(currElements, total_cnt)

}The final merge will looks like this:

override def merge(b1: Reservoir[T], b2: Reservoir[T]): Reservoir[T] = {

val (left, right) = if (b1.seq.size > b2.seq.size) {

(b1, b2)

} else {

(b2, b1)

}

if (left.elements < size) {

mergeTwoPartial(left, right)

} else if (right.elements < size) {

mergePartialRight(left, right)

} else {

mergeFull(left, right)

}

}Also we need to implement some additional required methods, used to serialize the state, an output and a finish method.

override def finish(reduction: Reservoir[T]): Seq[T] = reduction.seq.toSeq

override def bufferEncoder: Encoder[Reservoir[T]] = Encoders.product

override def outputEncoder: Encoder[Seq[T]] = ExpressionEncoder[Seq[T]]()From now we have a Reservoir Sampling algorithm implemented as a Spark aggregation function. I'm not sure it is safe, but on my single-node tests it works as expected.

Trait for Random Walks

As I already mentioned, there are a lot of possible improvements and trick in Random Walks algorithm. Some of them does not compatible with each other. As well, the target goal is vertex representations, not walks themselves. And finally, GraphFrames is a library by the end. So, it sounds like a good idea to add an abstraction with core logic and flexibility for anyone, who wants to implement it's own.

package org.graphframes.rw

import org.apache.spark.sql.DataFrame

import org.apache.spark.sql.Encoders

import org.apache.spark.sql.functions.array_union

import org.apache.spark.sql.functions.col

import org.apache.spark.sql.functions.udaf

import org.apache.spark.sql.graphframes.expressions.ReservoirSamplingAgg

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.ByteType

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.IntegerType

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.LongType

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.ShortType

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.StringType

import org.graphframes.GraphFrame

import org.graphframes.GraphFramesUnsupportedVertexTypeException

import org.graphframes.Logging

import org.graphframes.WithIntermediateStorageLevel

import scala.util.Random

trait RandomWalkBase extends Serializable with Logging with WithIntermediateStorageLevel {

protected var maxNbrs: Int = 50

protected var graph: GraphFrame = null

protected var numWalksPerNode: Int = 5

protected var batchSize: Int = 10

protected var numBatches: Int = 5

protected var useEdgeDirection: Boolean = false

protected var globalSeed: Long = 42L

protected var temporaryPrefix: Option[String] = None

protected var runID: String = ""

}Let's briefly describe configuration fields. The first one, maxNbrs, is a limit for the reservoir sampling. graph is a link the GraphFrame itself. As I already mentioned, the best way is to run multiple parallel and independent walkers, so the numWalksPerNode shows how much independent walkers should start from each vertex of the graph. May be I will change this in the future, because for some graphs it makes sense to run walkers not from each node. batchSize is just an amount of walker steps inside each batch and the numBatches is an amount of supersteps. For example, with batchSize = 10 and numBatches = 5 we will end with random walks of the length 50. globalSeed is used internally to generate random seeds for each batch. As I already mentioned, I made a decision to offload batches to the storage (in the form of Parquet tables), so it is required from the user to provide a temporaryPrefix for that. And runID is just for logging and generating of the parquet dataset names in temporary folder. I won't provide the code for all the setters and getters of these hyperparameters to avoid complication the post.

Preparation step that is run in each batch

On each step the sampling of neighbors needs to be run. Because for the most of implementation of walkers it will be the same, it makes sense to provide a default reference implementation. Because our reservoir sampling implementation is typed, I ended with this ugly pattern matching on the input vertex type. While it is not mentioned anywhere in the GraphFrames documentation, the scope of supported types for IDs is limited by Int, Long and String types actually.

protected def prepareGraph(): GraphFrame = {

val preAggs = if (useEdgeDirection) {

graph.edges

.select(col(GraphFrame.SRC), col(GraphFrame.DST))

.groupBy(col(GraphFrame.SRC).alias(GraphFrame.ID))

} else {

graph.edges

.select(GraphFrame.SRC, GraphFrame.DST)

.union(graph.edges.select(GraphFrame.DST, GraphFrame.SRC))

.distinct()

.groupBy(col(GraphFrame.SRC).alias(GraphFrame.ID))

}

val vertices = graph.vertices.schema(GraphFrame.ID).dataType match {

case StringType =>

preAggs.agg(

udaf(ReservoirSamplingAgg[java.lang.String](maxNbrs), Encoders.STRING)

.apply(col(GraphFrame.DST))

.alias(RandomWalkBase.nbrsColName))

case ShortType =>

preAggs.agg(

udaf(ReservoirSamplingAgg[java.lang.Short](maxNbrs), Encoders.SHORT)

.apply(col(GraphFrame.DST))

.alias(RandomWalkBase.nbrsColName))

case ByteType =>

preAggs.agg(

udaf(ReservoirSamplingAgg[java.lang.Byte](maxNbrs), Encoders.BYTE)

.apply(col(GraphFrame.DST))

.alias(RandomWalkBase.nbrsColName))

case IntegerType =>

preAggs.agg(

udaf(ReservoirSamplingAgg[java.lang.Integer](maxNbrs), Encoders.INT)

.apply(col(GraphFrame.DST))

.alias(RandomWalkBase.nbrsColName))

case LongType =>

preAggs.agg(

udaf(ReservoirSamplingAgg[java.lang.Long](maxNbrs), Encoders.LONG)

.apply(col(GraphFrame.DST))

.alias(RandomWalkBase.nbrsColName))

case _ => throw new GraphFramesUnsupportedVertexTypeException("unsupported vertex type")

}

val edges = graph.edges

GraphFrame(vertices, edges)

}In the case graph is directed, it is enough to group by only by src. If not, we need first to reverse and deduplicate edges and then do a group by operation. Our ReservoirSamplingAgg is used with Spark's builtin udaf (User Defined Aggregation Function). I'm not sure that explicit specification of Encoder is actually required but decided to keep it.

Abstract method for batch

That is left to the implementation, so just an interface.

protected def runIter(

graph: GraphFrame,

prevIterationDF: Option[DataFrame],

iterSeed: Long): DataFrameTop level method to run batches and combine results

Now we have everything and we need just to write iterations and combine results at the end.

def run(): DataFrame = {

if (graph == null) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Graph is not set")

}

if (temporaryPrefix.isEmpty) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Temporary prefix is required for random walks.")

}

runID = java.util.UUID.randomUUID().toString

logInfo(s"Starting random walk with runID: $runID")

val iterationsRng = new Random()

iterationsRng.setSeed(globalSeed)

val spark = graph.vertices.sparkSession

for (i <- 1 to numBatches) {

logInfo(s"Starting batch $i of $numBatches")

val iterSeed = iterationsRng.nextLong()

val preparedGraph = prepareGraph()

val prevIterationDF = if (i == 1) { None }

else {

Some(spark.read.parquet(iterationTmpPath(i - 1)))

}

val iterationResult: DataFrame = runIter(preparedGraph, prevIterationDF, iterSeed)

iterationResult.write.parquet(iterationTmpPath(i))

}

logInfo("Finished all batches, merging results.")

var result = spark.read.parquet(iterationTmpPath(1))

for (i <- 2 to numBatches) {

val tmpDF = spark.read

.parquet(iterationTmpPath(i))

.withColumnRenamed(RandomWalkBase.rwColName, "toMerge")

result = result

.join(tmpDF, Seq(RandomWalkBase.walkIdCol))

.select(

col(RandomWalkBase.walkIdCol),

array_union(col(RandomWalkBase.rwColName), col("toMerge"))

.alias(RandomWalkBase.rwColName))

}

result = result.persist(intermediateStorageLevel)

val cnt = result.count()

resultIsPersistent()

logInfo(s"$cnt random walks are returned")

result

}Materialization at the end is required because I'm considering to clean up the temporary folder at the end. Without persisting in memory deleting data after it's reading will break Spark's lazy nature. I was also thinking about checkpoints in the middle of the chain read + join, but I don't think it should be a problem up to 10-15 batches. If anyone needs more, a better strategy would be to increase the batch size instead.

Random Walks with Restart

The first and the only present at the moment implementation is a simple Random Walks with Restart. While it is still a 1st order algorithm, based on the papers and reviews I read it is one of the best in terms of balance between scalability and quality. Compared to the RandomWalkBase trait it will have one additional hyperparameter: the restart probability.

package org.graphframes.rw

import org.apache.spark.sql.DataFrame

import org.apache.spark.sql.functions.*

import org.graphframes.GraphFrame

class RandomWalkWithRestart extends RandomWalkBase {

private var restartProbability: Double = 0.1

}And finally the concrete implementation.

override protected def runIter(

graph: GraphFrame,

prevIterationDF: Option[DataFrame],

iterSeed: Long): DataFrame = {

val neighbors = graph.vertices.select(col(GraphFrame.ID), col(RandomWalkBase.nbrsColName))

var walks = if (prevIterationDF.isEmpty) {

graph.vertices.select(

col(GraphFrame.ID).alias("startingNode"),

col(GraphFrame.ID).alias(RandomWalkBase.currVisitingVertexColName),

explode(

when(

array_size(col(RandomWalkBase.nbrsColName)) > lit(0),

array((0 until numWalksPerNode).map(_ => uuid()): _*)).otherwise(array()))

.alias(RandomWalkBase.walkIdCol),

array(col(GraphFrame.ID)).alias(RandomWalkBase.rwColName))

} else {

prevIterationDF.get.select(

col("startingNode"),

col(RandomWalkBase.currVisitingVertexColName),

col(RandomWalkBase.walkIdCol),

array(col(RandomWalkBase.currVisitingVertexColName)).alias(RandomWalkBase.rwColName))

}

for (_ <- (0 until batchSize)) {

walks = walks

.join(

neighbors,

col(GraphFrame.ID) === col(RandomWalkBase.currVisitingVertexColName),

"left")

.withColumn("doRestart", rand() <= lit(restartProbability))

.withColumn(

"nextNode",

when(col("doRestart"), col("startingNode")).otherwise(

element_at(shuffle(col(RandomWalkBase.nbrsColName)), 1)))

.select(

col(RandomWalkBase.walkIdCol),

col("startingNode"),

col("nextNode").alias(RandomWalkBase.currVisitingVertexColName),

array_append(

col(RandomWalkBase.rwColName),

col(RandomWalkBase.currVisitingVertexColName)).alias(RandomWalkBase.rwColName))

}

walks

}Here I'm using Spark's uuid to generate walks ID on the first iteration (the case when prevIterationDF is empty). Unfortunately spark does not have a built-in choice function to choose the random element from the array, so I just used shuffle + taking the first element. In the case of the restart we are just moving walker to the starting node (and that is reason why we need to keep it).

From sequence to representations

Now we can generate a sequence of vertices from Random Walks. I run some tests and it works pretty fast. Yes, a small problem with huge offload to disks, but with S3/HDFS should not be. Also it should be scalable from the first look, because there is nothing special. Arrays of the reasonable length are processed by spark quite good and the sampling trick should solve the skew curse.

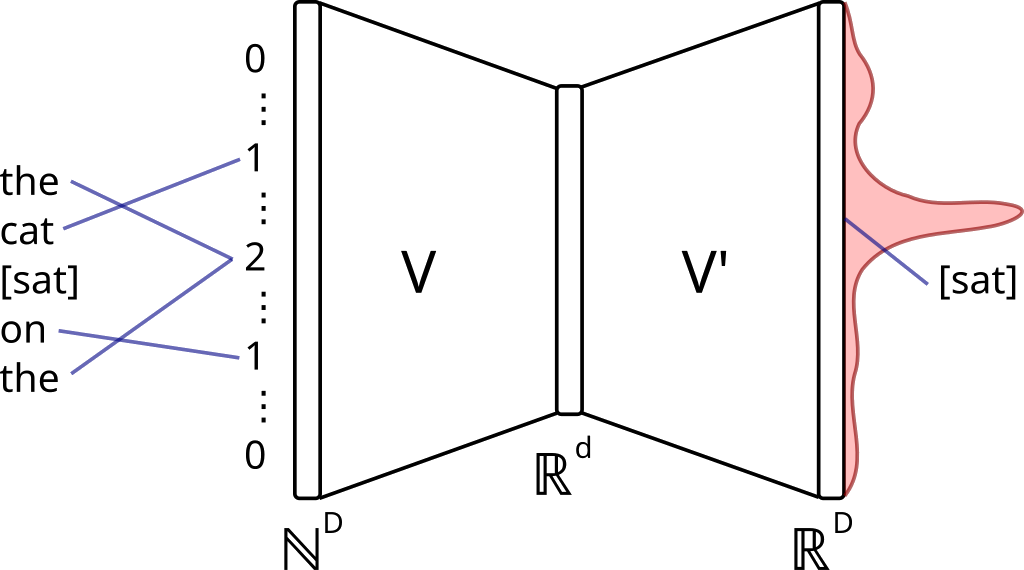

Word2vec

But what's next? The goal was to get representations, not just sequences. How to go from sequence to embeddings? And the simplest answer is Word2vec. It is a way to learn the representations by optimizing the similarity of often co-occurred items in sequences. It takes the sequences of elements (words, items, vertices, etc.) and train the vocabulary as the Map[String, Array[Double]].

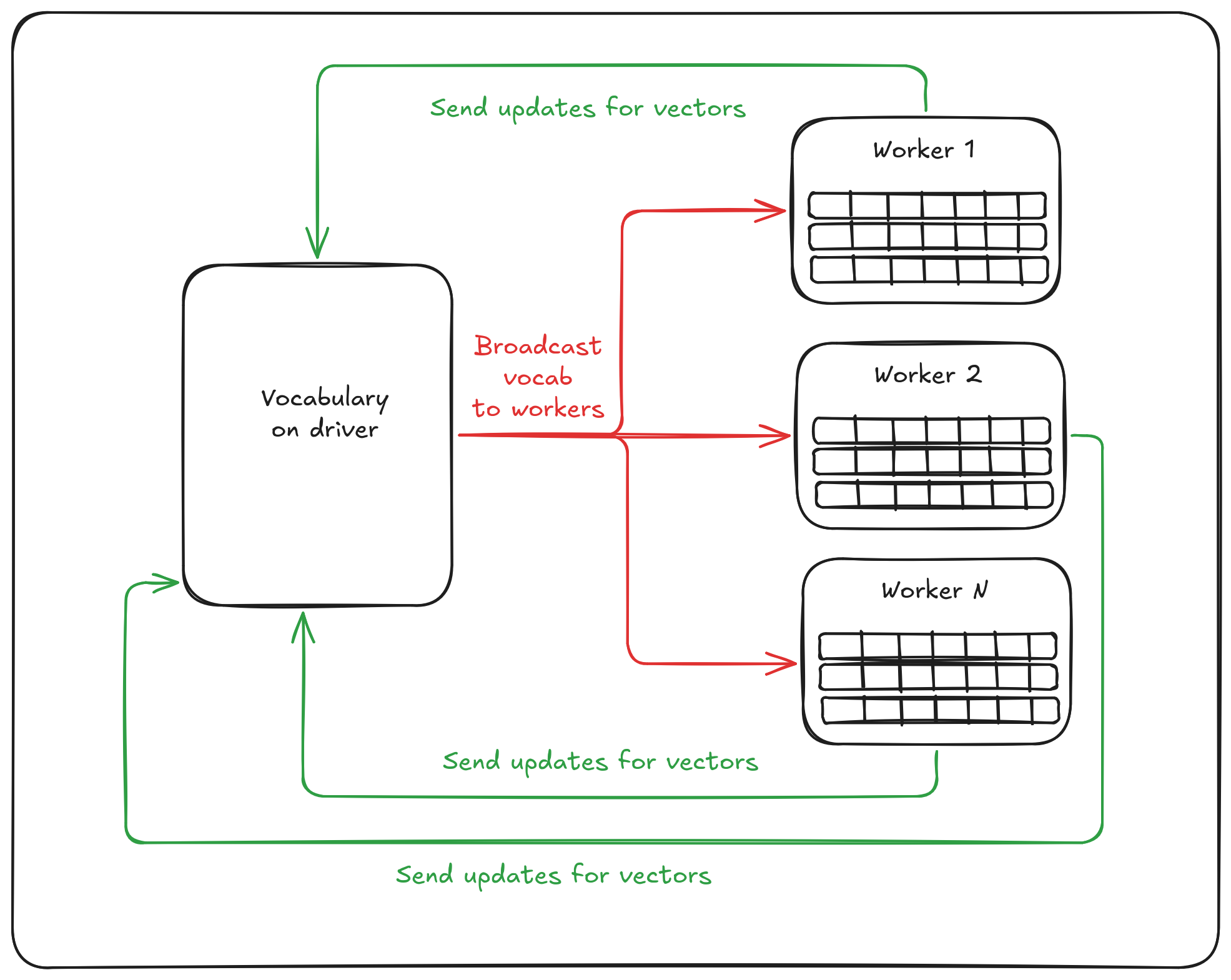

There are a lot of educational materials about Word2vec model and modifications, so I won't stop on the details. One important thing to mention is that word2vec required "learning" of the vertex representations. Let's see how the distributed word2vec works in Apache Spark MLLib (there is also a word2vec in the Apache Spark ML, but it is just a wrapper). It creates the global vocabulary of all the words (or vertices in our case) and their initial vectors. It is done on the Spark's driver.

val words = dataset.flatMap(x => x)

vocab = words.map(w => (w, 1))

.reduceByKey(_ + _)

.filter(_._2 >= minCount)

.map(x => VocabWord(

x._1,

x._2,

new Array[Int](MAX_CODE_LENGTH),

new Array[Int](MAX_CODE_LENGTH),

0))

.collect()

.sortBy(_.cn)(Ordering[Long].reverse)After that (and some additional magic that I will skip) the vocabulary is broadcasted from driver to workers that process each own subset of sequences. On the reduce step workers send their updates for the vocabulary to driver that do all-reduce operation. And this steps are repeated until convergence (or until the numIterations reached).

During my research, I checked existing implementations of random-walk based embeddings on Spark. All of them are generating sequences from Random Walks in one or another way and at the end just put these sequences to Spark's Word2vec:

For example, that is the code from the Mercury Graph project.

w2v = Word2Vec(

vectorSize=self.dimension,

maxIter=self.w2v_max_iter,

numPartitions=self.w2v_num_partitions,

stepSize=self.w2v_step_size,

inputCol="random_walks",

outputCol="model",

minCount=self.w2v_min_count,

)

self.node2vec_ = w2v.fit(self.paths_)I cannot try to blame anyone for using such an approach because it works. The main issue is scalability of it to the real-world graphs with billions of vertices… The story is that Word2vec itself as well as its implementation in Apache Spark were designed to solve a different problem. The algorithm was created for Natural Language Processing (NLP). And the story is there is a natural limitations for the problems size. An amount of words in languages are barely hit a million of unique items. The Oxford English Dictionary provides even a smaller estimation, like \(\simeq 500000\) of unique words. But in the graph worlds, 500000 of vertices is a small-medium sized graph. For example, we are running benchmarks of GraphFrames inside GitHub action agents on the graph with 2M of vertices that is already much more than amount of possible words in English.

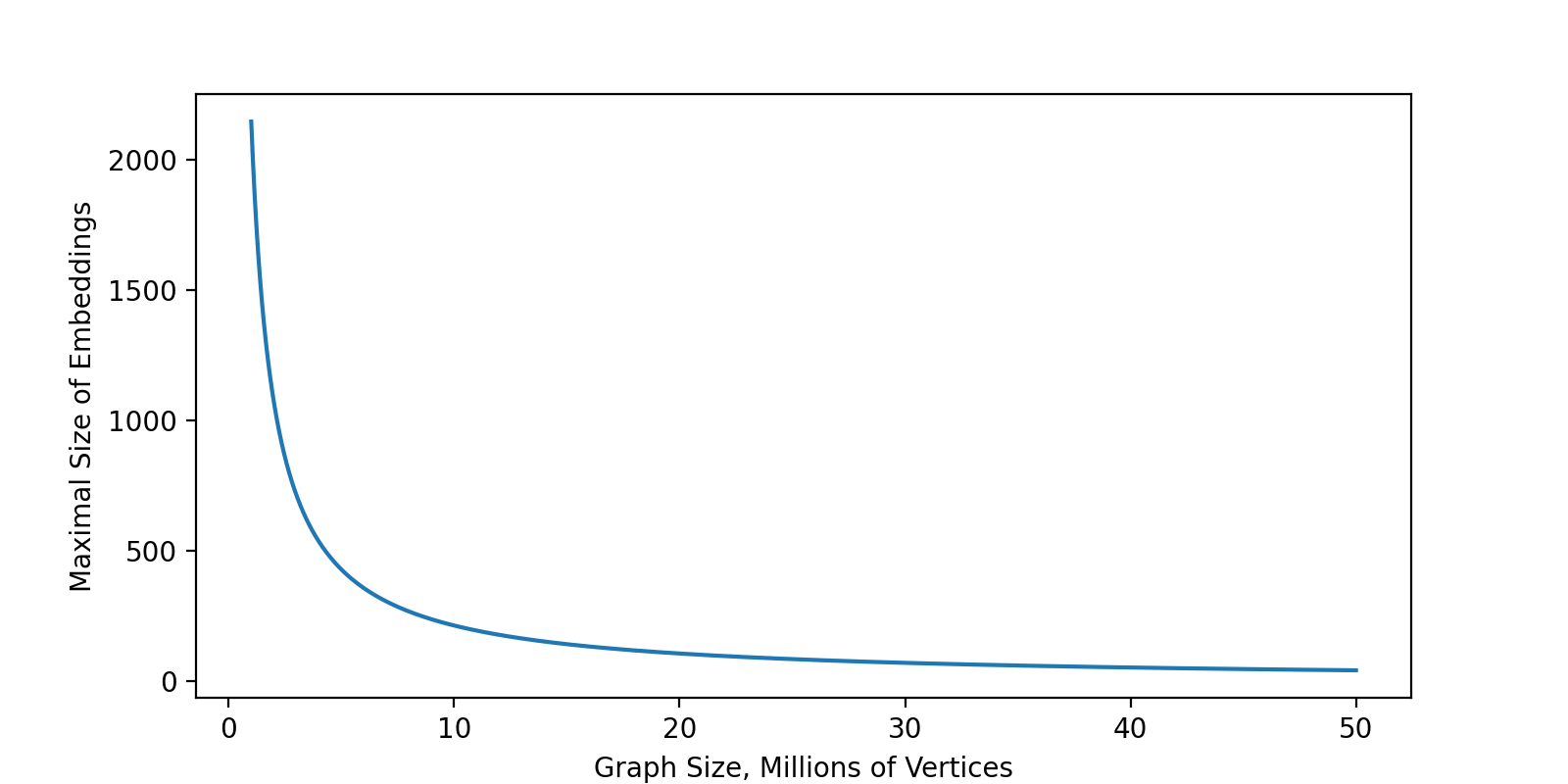

While it is really hard to imagine a Spark driver that can handle a hash map of the size of ten millions of keys and Array[Double] of the length 100 as values, there is a more explicit limitation. Let's examine the code of Spark's Word2vec again and take a look on this line:

if (vocabSize.toLong * vectorSize >= Int.MaxValue) {

throw new RuntimeException("Please increase minCount or decrease vectorSize in Word2Vec" +

" to avoid an OOM. You are highly recommended to make your vocabSize*vectorSize, " +

"which is " + vocabSize + "*" + vectorSize + " for now, less than `Int.MaxValue`.")

}In other words, the size of vocabulary multiplied by the size of embeddings should be less than Int.MaxValue. It leads to the following picture where on the X-axis is an amount of the vertices in the graph and on the Y-axis is the maximal possible size of embeddings.

For example, the default size of embeddings in Spark is 100 that means you can process graphs up to \(\simeq 21.6 \cdot 10^6\) vertices. If your graph has 1B of vertices, the best you can learn is embeddings of the size 2… Is 2 float numbers enough to encode the information about 1B of vertices? I barely think so. Moreover, if you are working with a graph with a couple of millions of vertices you barely need GraphFrames, Spark and distributed graph processing, because such a size is much easier to process on a single node.

Alternatives to Word2vec

While it is possible to left Word2vec as an option for users of GraphFrames, it is obvious that the library requires more scalable solutions. I read more than 15 different papers with alternative approaches and my group them in the following way.

- Parameter Server based solutions

- Hashing trick based solutions

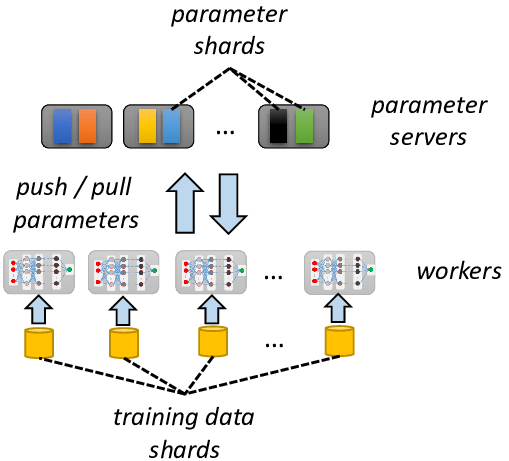

Parameter Server Architecture

Parameter Server (PS) architecture is a way to train models like Word2vec without limitations. Instead of using Spark driver for keeping the whole vocabulary and do all-reduce, we are creating a separate Parameter Server that is a Key-Value store in the simplest scenario. With a PS we do not need to materialize the huge vocabulary, instead we can store it offloaded and send to workers only what is actually required.

While such an approach is the industry standard, it is not a fit for GraphFrames that aims to bring Graph Machine Learning on top of existing infrastructure. If the strong engineering teem can maintain a Parameter Server they just do not need GraphFrames. And I cannot realize how I can add a Parameter Server "without server" on top of existing Spark Clusters.

Hashing Trick

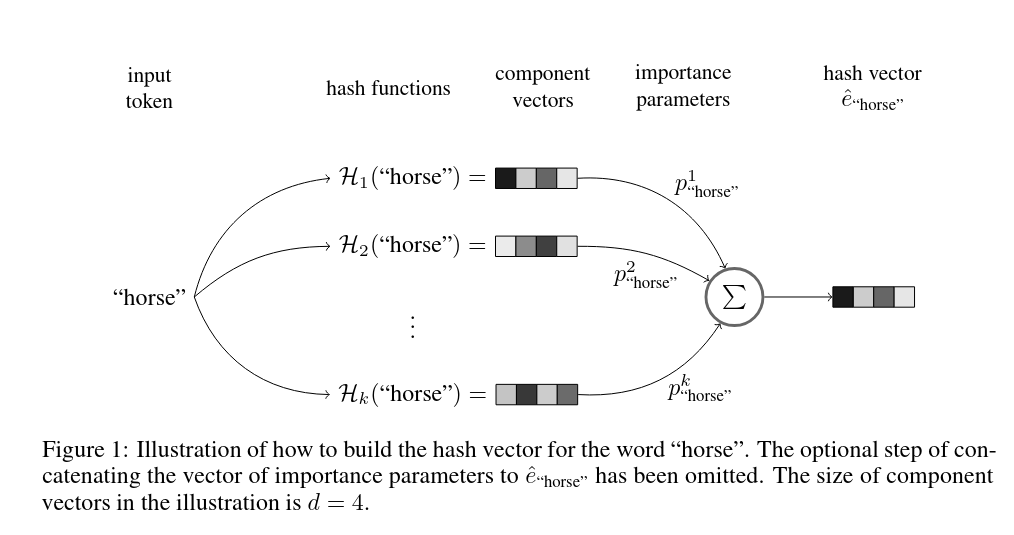

Another possible direction is to try to reduce the vocabulary size to fit it into the driver. Hashing Trick is an attempt to make elements in vocabulary sharable for different elements of sequences. The key work is Tito Svenstrup, Dan, Jonas Hansen, and Ole Winther. "Hash embeddings for efficient word representations." Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017). It suggest the idea of applying multiple hash function to each element to map it into few buckets and the final representation of element in that case is a weighted sum of buckets embeddings.

This is already feasible to implement on Spark beside the fact it would require to write Word2vec from scratch with a lot of complications. Maybe one day there will be a true hashing-trick in GraphFrames, at the moment I'm not ready to do it. My knowledge of linear algebra and hard math is quite a limited.

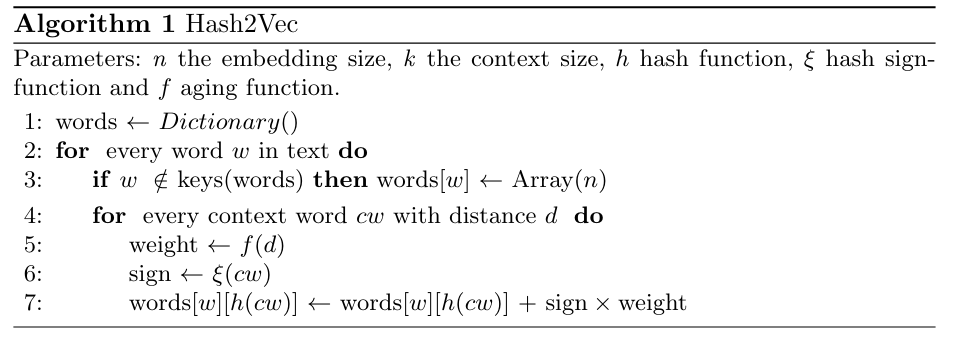

Hash2vec

But what we can learn from the hashing trick is the direction. And reading one paper after another I finally found one that looks like a perfect balance between scalability and feasibility of the implementation. It is a work Tito Svenstrup, Dan, Jonas Hansen, and Ole Winther. "Hash embeddings for efficient word representations." Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017). The work itself is based on the well known theory of Random Projections that states, that random projections preserve the distances.

Algorithm itself is very-very simple and works in linear time (actually just in a single pass over data). As well the approach does not require any kind of global shared vocabulary: each sequence of the dataset can be processed independently and final vectors of elements can be done in a single all-reduce step.

Implementation with Spark

Let's start as usual from imports and the arguments definition.

package org.graphframes.embeddings

import org.apache.spark.ml.linalg.SQLDataTypes.VectorType

import org.apache.spark.ml.linalg.Vectors

import org.apache.spark.ml.stat.Summarizer

import org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD

import org.apache.spark.sql.DataFrame

import org.apache.spark.sql.Row

import org.apache.spark.sql.functions.col

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.ArrayType

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.ByteType

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.IntegerType

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.LongType

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.ShortType

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.StringType

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.StructField

import org.apache.spark.sql.types.StructType

import org.apache.spark.unsafe.hash.Murmur3_x86_32.*

import org.apache.spark.unsafe.types.UTF8String

import org.graphframes.GraphFramesUnsupportedVertexTypeException

import org.graphframes.rw.RandomWalkBase

import scala.annotation.nowarn

import scala.jdk.CollectionConverters.*

import scala.reflect.ClassTag

class Hash2Vec extends Serializable {

private var contextSize: Int = 5

private var numPartitions: Int = 5

private var embeddingsDim: Int = 256

private var sequenceCol: String = RandomWalkBase.rwColName

private var decayFunction: String = "gaussian"

private var gaussianSigma: Double = 1.0

private var hashingSeed: Int = 42

private var signHashingSeed: Int = 18The contextSize is just a size of the sliding window. numPartitions is how much workers to we want to have. More workers means less peak memory usage but more work on the all-reduce step. embeddingsDim is the size of embeddings vector. As all the algorithms based on the Random Projections theory, Hash2vec produces very sparse vectors, so it is strongly recommend to use at least 256 but better to have something like 1024. To map hash to index in the embedding vector I will use modulo operation, so having embeddings size equal to some power of 2 is strongly recommended from the performance point of view. sequenceCol is just a name of the column of the Spark DataFrame that contains sequences. In our case it is a result of Random Walks, but actually this algorithm can be used to produce embeddings from anything (user-items, words, etc.) decayFunction has at the moment two options. One is a constant when all the elements from the window generate the same impact, the second is gaussian when closer elements make more. Gaussian function can be configured by the gaussianSigma argument. I will use Spark's built-in implementation of the MurMur3 hash and to allow users to try different hashing, both index, and sign hashing functions are defined be seeds.

I copied some parts of the code from the Spark built-in HashingTF. This are nonNegativeMode and hashFunc:

private def nonNegativeMod(x: Int, mod: Int): Int = {

val rawMod = x % mod

rawMod + (if (rawMod < 0) mod else 0)

}

private def hashFunc(term: Any, seed: Int): Int = {

term match {

case null => seed

case b: Boolean => hashInt(if (b) 1 else 0, seed)

case b: Byte => hashInt(b.toInt, seed)

case s: Short => hashInt(s.toInt, seed)

case i: Int => hashInt(i, seed)

case l: Long => hashLong(l, seed)

case f: Float => hashInt(java.lang.Float.floatToIntBits(f), seed)

case d: Double => hashLong(java.lang.Double.doubleToLongBits(d), seed)

case s: String =>

val utf8 = UTF8String.fromString(s)

hashUnsafeBytes(utf8.getBaseObject, utf8.getBaseOffset, utf8.numBytes(), seed)

case _ =>

throw new GraphFramesUnsupportedVertexTypeException(

"Hashing2vec with murmur3 algorithm does not " +

s"support type ${term.getClass.getCanonicalName} of input data.")

}

}Constant window function is trivial but Gaussian is not so hard to implement too:

private def decayGaussian(d: Int, sigma: Double): Double = {

math.exp(-(d * d) / (sigma * sigma))

}Initially I was thinking about processing each sequence in the atomic way and after that merge all the results. But I realized very fast, that in that case the group by will blow the cluster. Just to understand, if the graph has 1B of vertices, with default arguments we will have 5B of walks of the size 50. If we assume that in each sequence only half of elements are unique, we will get \(\simeq 25\) vectors from each walk. After exploding we will finish with the dataset with 75 billions of rows and these rows are quite big because they are vectors of size 256. Group By by the element id will trigger the whole shuffle of this and most probably the cluster will die here. RIP.

So, I decided to implement in a lower level with mapPartitions and instead of constructing the map from elements to vectors on each row, I will produce it once per partition. Yes, there may be some loss in parallelism, but at the same time it will significantly reduce the amount of shuffle on the all-reduce step. So, let's do it with RDD and mapPartitions.

private def processPartition[T](iter: Iterator[Seq[T]]): Iterator[(T, Array[Double])] = {

val localVocab = new java.util.concurrent.ConcurrentHashMap[T, Array[Double]]()

for (seq <- iter) {

val currentSeqSize = seq.length

for (idx <- (0 until currentSeqSize)) {

val currentWord = seq(idx)

if (!localVocab.containsKey(currentWord)) {

localVocab.put(currentWord, Array.fill(embeddingsDim)(0.0))

}

val context = ((idx - contextSize) to (idx + contextSize)).filter(i =>

(i >= 0) && (i < currentSeqSize) && (i != idx))

for (cIdx <- context) {

val word = seq(cIdx)

val weight = weightFunction(math.abs(cIdx - idx))

val sign = 2.0 * signHash(word) - 1.0

val embeddingIdx = valueHash(word)

val currentEmbedding = localVocab.get(currentWord)

currentEmbedding(embeddingIdx) += sign * weight

}

}

}

localVocab

.entrySet()

.asScala

.map(entry => (entry.getKey(), entry.getValue()))

.iterator

}As you may see, it is just line-by-line implementation of the algorithm from the original paper! Such a nested for-loops should be JIT friendly, so the Java compiler (C2) can be able to effectively use SIMD here in runtime. At least I hope so :)

Because our RDD way is typed, but spark DataFrames are not, we need to write a couple more things.

private def runTyped[T: ClassTag](data: DataFrame): RDD[(T, Array[Double])] = {

data

.select(col(sequenceCol))

.rdd

.map(_.getAs[Seq[T]](0))

.repartition(numPartitions)

.mapPartitions(processPartition[T])

}And finally the all-reduce step when we just compute a sum of all the vectors.

def run(data: DataFrame): DataFrame = {

val spark = data.sparkSession

require(data.schema(sequenceCol).dataType.isInstanceOf[ArrayType], "sequence should be array")

val elDataType = data.schema(sequenceCol).dataType.asInstanceOf[ArrayType].elementType

weightFunction = decayFunction match {

case "gaussian" => (d: Int) => decayGaussian(d, gaussianSigma)

case "constant" => (_: Int) => 1.0

case _ => throw new RuntimeException(s"unsupported decay functions $decayFunction")

}

valueHash = (el: Any) => nonNegativeMod(hashFunc(el, hashingSeed), embeddingsDim)

signHash = (el: Any) => nonNegativeMod(hashFunc(el, signHashingSeed), 2)

val (rowRDD, schema) = elDataType match {

case _: StringType =>

(

runTyped[String](data).map(f => Row(f._1, Vectors.dense(f._2))),

StructType(Seq(StructField("id", StringType), StructField("vector", VectorType))))

case _: ByteType =>

(

runTyped[Byte](data).map(f => Row(f._1, Vectors.dense(f._2))),

StructType(Seq(StructField("id", ByteType), StructField("vector", VectorType))))

case _: ShortType =>

(

runTyped[Short](data).map(f => Row(f._1, Vectors.dense(f._2))),

StructType(Seq(StructField("id", ShortType), StructField("vector", VectorType))))

case _: IntegerType =>

(

runTyped[Int](data).map(f => Row(f._1, Vectors.dense(f._2))),

StructType(Seq(StructField("id", IntegerType), StructField("vector", VectorType))))

case _: LongType =>

(

runTyped[Long](data).map(f => Row(f._1, Vectors.dense(f._2))),

StructType(Seq(StructField("id", LongType), StructField("vector", VectorType))))

case _ =>

throw new GraphFramesUnsupportedVertexTypeException(

s"Hash2vec supports only string or numeric types of elements but gor ${elDataType.toString()}")

}

spark.createDataFrame(rowRDD, schema).groupBy("id").agg(Summarizer.sum(col("vector")).alias("embedding"))

}I did not write comprehensive tests for all the corner cases, but on the evaluation and performance checks it works. It is order of magnitude faster compared to the Spark Word2vec, as well it is horizontally scalable. There are no global vocabulary, driver load or something. For huge graphs people should just tune the amount of partitions as a balance between the size of in-partition vocab and an amount of work at the all-reduce step.

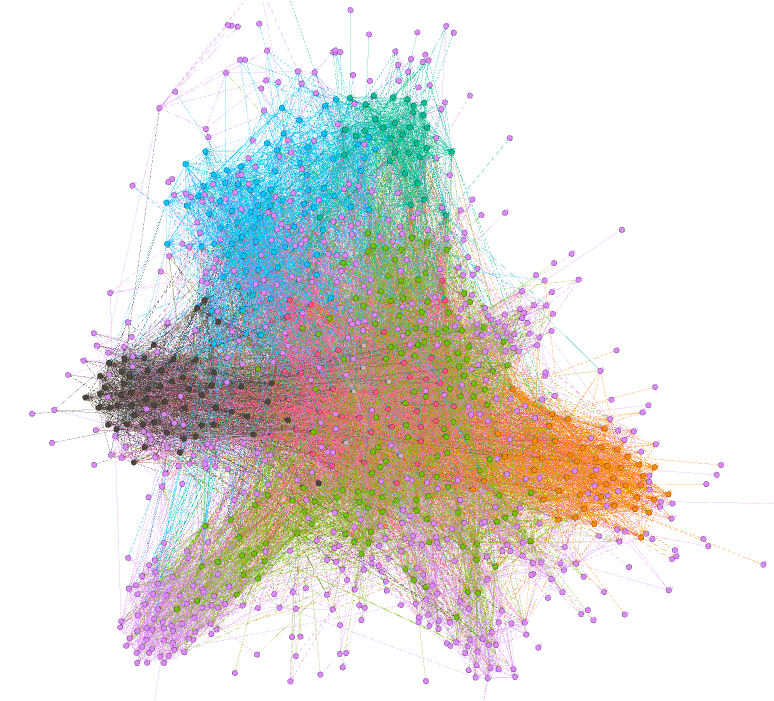

Performance analysis

The first thing I did was computing embeddings from my Hash2vec implementation, run k-means clustering on top and put results to the Gephi. And you know what? It really works. Not perfect, but look, we just got a "free" graph embeddings in \(O(N)\)!

Classification power

But generating cool pictures in Gephi is barely a goal of anyone who is going to use GraphFrames. The fair approach is to check how much predictive power on ML tasks. I took a few graphs from the Karateclub Project. This graphs are small but they a) fit into my laptop b) have classification targets. For all of them I generated embeddings with both, Hash2vec and Word2vec. To check the power of embeddings instead of power of ML classifier I used a K-Nearest-Neighbor algorithm with cosine similarity functions. It just compute the distances between elements, take K nearest neighbors of each and use an average of their targets as a prediction. For evaluation I used Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC-AUC) metric that can be explained in the following way. If we range all our predictions by the predicted score, the ROC-AUS shows the probability that a random element with label 1 will have a score bigger than a random element with label 0. ROC-AUC was computed on cross-validation. That are results:

| Test Case | Word2vec | Hash2vec |

|---|---|---|

| github | 0.77 | 0.61 |

| lastfm | 0.88 | 0.71 |

| 0.95 | 0.83 |

As you can see while Hash2vec provides some prediction power, Word2vec outperforms it significantly. I'm not sure may it be the problem with huge dispersion of L2 norms of Hash2vec vectors because I did not apply normalization. Just for understanding, the norm of Hash2vec vectors is proportional to the vertex degree while norm of the Word2vec vectors should distributed equally. I will discuss this in the next section, but as you can see, Hash2vec already has a predictive power, even without normalization!

Whats next?

Write tests, create PySpark bindings and merge it to GraphFrames

While there are a lot of space for improvements I need to stop here. The Pull Request is already 1000 lines of the Scala code. I think having almost free to compute graph embeddings from Random Walks is an excellent starting point for the project.

I need also to write tests for corner cases, write the documentation. And the most boring but required part is to write PySpark bindings for this new API because Scala is nice for the low-level Spark, but people and especially Data Scientists prefer to work with Python. It would be natural to propose Hash2vec as an addition for SparkML. But I'm not sure that maintainer of the project are ready to accept anything new to the SparkML module. I'm not ready to jump into it without a shepherd. So, if by any chance you know any PMC of the project who can help to promote it, I'm willing to rewrite it according Spark standards and push.

Normalization

As I already mentioned, Hash2vec vectors are sparse and have L2 norm proportional to vertex degree. From one point of view, encoding the degree is important. From another, normalization may increase the prediction power. I'm going to at least add this option in the future. This is question that requires hard math knowledge, so I decided to postpone it.

Convolutions

I read recently two papers (The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Randomized Representations in Online Continual Graph Learning, On the Effectiveness of Random Weights in Graph Neural Networks) that give me the following idea. The main problem of Hash2vec embeddings is that they are very "noisy". But what if we smooth them by applying a GraphSAGE like convolution on top with fixed random weights? Because it does not require any kind of training it may be done in Spark with a pure BLAS operations. Can't say it will be easy, but it sounds feasible at least. In my mind, the convolution layer with random weights should add some local information to embeddings. So, we will have the best of two worlds: deep structure information about the graph from Random Walks and local information from graph convolutions… Definitely worth trying I think.

Conclusion

In this post I showed how the graph embeddings can be generated at real-world graphs scale. While the quality of embeddings is not so good, for me it is better to have some embeddings instead of having nothing. I think that anyone who is building a recommender system can combine Hash2vec embeddings and, for example, Spark ALS implementation because they are based on different information. As well, such an embeddings can be easily added to classifications pipelines.

I hope it was interesting for you to read :)