TLDR

OSS Vanilla Spark is a multi-purpose engine designed to handle different kinds of workloads. Under the hood, Spark uses data-centric code generation but also has vectorization as well as an option to fall back to a pure Volcano-mode. This hybrid approach allows Spark to be a truly unified and multi-purpose distributed query engine that can handle both OLAP workloads on top of classical data warehouses as well as effectively process semi-structured data, logs, etc. with complex logic including nested conditions, null handling, and heterogeneous row structures.

However, there is a price for being unified. Because of its hybrid nature, OSS Vanilla Spark will almost always be slower compared to pure vectorized engines like Trino or Snowflake on OLAP workloads with columnar data, except in rare cases involving large amounts of nulls or deep branching in queries. So, the quick answer to why Apache Spark may be considered a slow engine for OLAP workloads on top of data stored in columnar format is that Apache Spark just was not designed specifically for these kinds of queries.

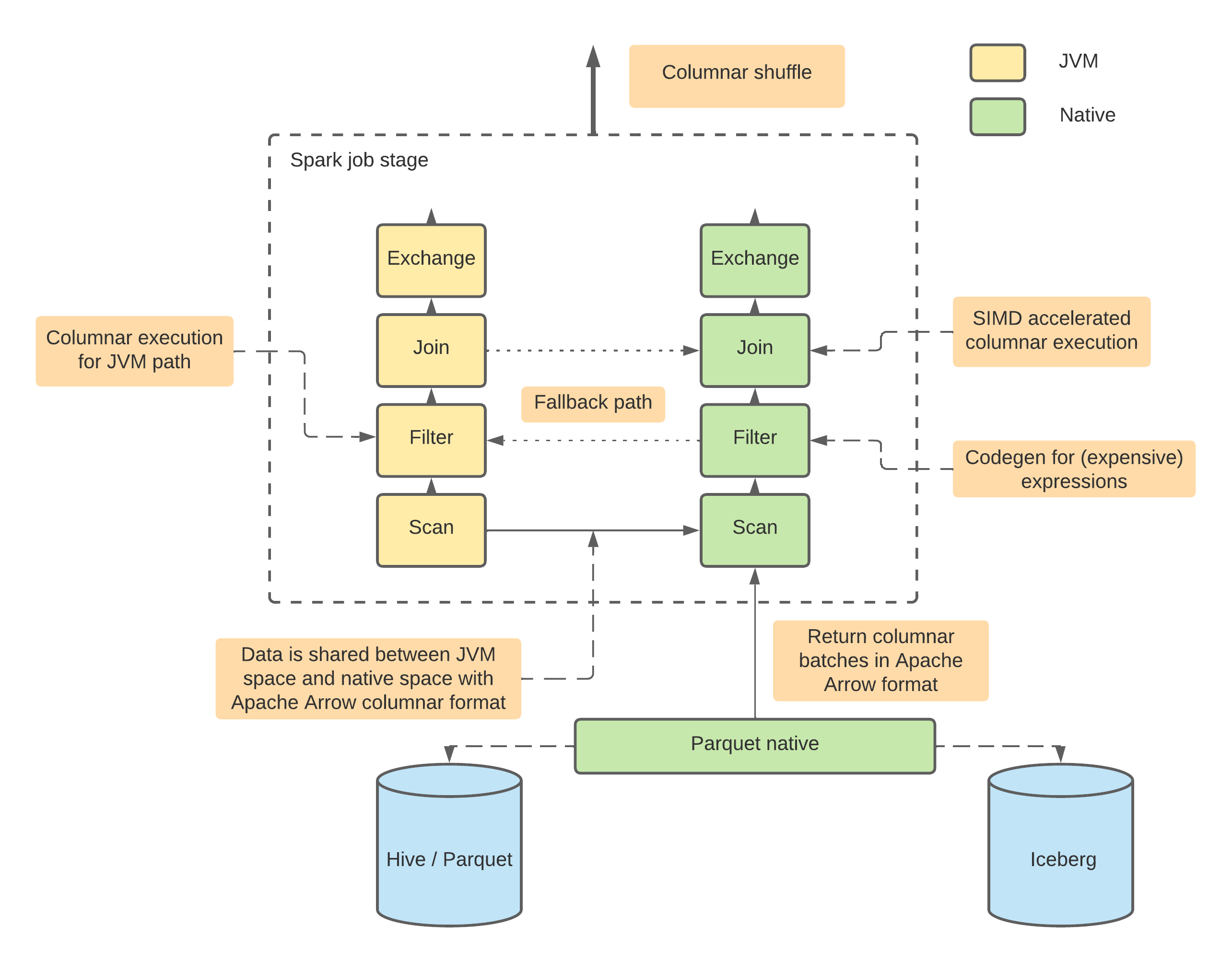

At the end of the post, I will also briefly touch on the topic of how OSS Spark can be transformed into a pure vectorized engine through Catalyst Extensions API and solutions like Databricks Photon, Apache Gluten (incubating), and Apache Datafusion Comet. All these solutions replace built-in data-centric code generation with vectorized execution using VeloxDB/ClickHouse in Gluten, Datafusion in Comet, or proprietary solution in Photon.

Preface & disclaimer

I'm not affiliated in any way with companies like Databricks that sell managed Apache Spark as a service. Similarly, I'm not affiliated with companies that sell Databricks' competitors such as Trino, Snowflake, and other OLAP solutions. However, I do work with Apache Spark in my daily job, and I am a maintainer of open source projects like GraphAr, GraphFrames, chispa, and spark-fast-tests that rely on Apache Spark. In this blog post, I'm trying to be as neutral as possible and avoid showing any preferences. Most of my statements are based on scientific publications referenced at the end of the post.

Introduction

This post will contain many concepts, such as columnar versus row storage and memory, volcano mode, code-generation, virtual function calls, etc. Most of the introduction will provide brief explanations of these concepts as well as links for further reading. If you are familiar with all these basic concepts, feel free to skip the introduction entirely. I have also tried to split the introduction into subsections to allow you to skip only specific concepts.

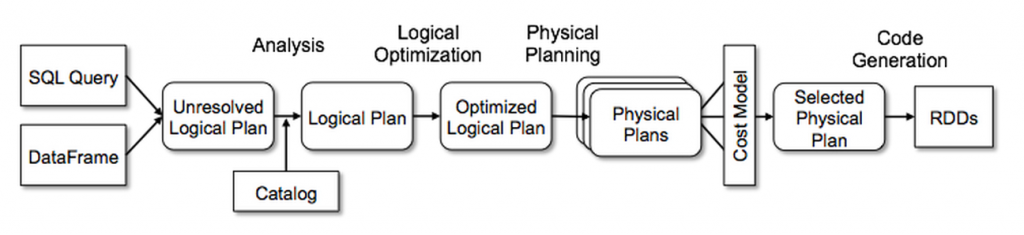

From SQL to Plan: before the physical execution

The first question we need to answer is what happens after you write your SQL query (or Python code) and click a "submit" button. Most modern distributed query engines follow the so-called lazy execution model (as opposed to the eager execution model used in, for example, the Pandas framework). Instead of immediately executing the code the user wrote, an engine appends the user's instruction to the end of a Plan. A Plan is actually just a sequence of instructions like "read this data," "filter the data by this column," "join these two datasets," "group by and aggregate," etc. So, by the time the user expects output from the engine—for example, when the user sends an instruction to write the result somewhere or insert it into a table—the query engine knows all the operations and instructions.

The main benefit of this approach is that the engine is able to find a more optimal order of execution compared to the order provided by the user [2]. For example, if a user sends instructions to read a dataset with 1,000 columns, then filter by one column, select three columns, and write to another table, the engine can easily realize there's no need to read all 1,000 just the three needed columns is sufficient. Another example: if a user sends instructions to apply a very expensive operation like regexp extraction on a column and then sends an instruction to filter the result by another column, an engine can re-order these instructions to reduce the amount of data before the expensive operation.

In the end, most query engines finish with a multi-step optimization of the user's execution Plan to create an optimized Plan. This is typically done by combining fixed rules, adaptive statistics from the data, and also by choosing the best approach based on the specific implementation of how the engine will process data at the physical level.

Row-by-row processing or so called Volcano-mode

When we have an optimized Logical Plan or a sequence of instructions, a query engine should plan and perform actual data transformations according to the plan. The simplest way to do this is by processing rows (also often called tuples) one by one, applying a chain of transformations to them. Such an approach is often called Iterator-mode or Volcano-mode, named after the solution where it was first introduced [2]. For example, if we have the following set of instructions ["read" -> "filter" -> "transform" -> "write"], we can write the following pseudo-code:

def read(path) -> Iterator[row]:

...

def filter_by_cond(input: Iterator[row], condition) -> Iterator[row]:

...

def transform_with_expr(input: Iterator[row], expression) -> Iterator[row]:

...

def write(input: Iterator[row], path) -> None:

...

write(

transform_with_expr(

filter_by_cond(

read(input_path),

cond,

),

expr,

),

output_path

)NOTE: This approach also illustrates well how Apache Spark worked before version 2.0 when the DataFrame API was introduced. If you are working with the RDD abstraction, rows will be processed exactly like this—one by one via chained function calls—with each function producing a new RDD, except for I/O functions.

While this approach is very simple and easy to both understand and implement, it is far from the most optimal way of data processing. The main problem is that with such an approach, an engine cannot benefit from modern CPU optimizations like caching. Another problem is that chained calls create overhead by themselves; for example, in Apache Spark RDDs, they may generate many temporary objects in memory that can lead to increased garbage collection.

Vectorized processing: MonetDB/X100

One of the biggest advantages of modern CPUs is their ability to execute the same instruction on multiple inputs simultaneously. This is called Single Instruction Multiple Data, or SIMD. How can a query engine benefit from this capability? Based on the disadvantages of Volcano-mode processing, the answer may already be obvious: instead of row-by-row processing, we should split our data into batches of rows and apply transformations and expressions to entire batches rather than applying them to individual rows in a loop [3].

But it may be more tricky than it appears at first glance. Let's focus on the already mentioned set of instructions ["read" -> "filter" -> "transform" -> "write"]. While read and write should be easy, filter and transform are not. The first question is how to filter out rows without losing all the SIMD benefits? The simplest solution would be to store not only rows, but also a binary mask of the same size as the rows batch itself. Such a mask can be updated along with the rows themselves.

For example, in the case of a filter operator, we may avoid deleting rows from the batch that is a) expensive and b) breaks vectorization, but just mark these rows as zeros in the bitmask. The same technique may be used for nulls handling (though this can be even more complex). In that case, the read operation can read the data, split it into batches, and also create a bitmask filled with ones for non-null rows and zeros for null rows.

After that, a filter expression can be computed in parallel and applied to all the rows in a batch, but instead of updating the batch, it will update only the bitmask. The next step, transformation, can be applied to all the rows in a batch again. And finally, the write operator will write only rows that are marked by ones in the bitmask.

@dataclass

class BatchOfRows:

num_rows: int

rows: Sequence[row]

null_mask: Sequence[row]

def read(path) -> Iterator[BatchOfRows]:

...

def filter_by_cond(input: Iterator[BatchOfRows], condition) -> Iterator[BatchOfRows]:

...

def transform_with_expr(input: Iterator[BatchOfRows], expression) -> Iterator[BatchOfRows]:

...

def write(input: Iterator[batchOfRows], path) -> None:

...

write(

transform_with_expr(

filter_by_cond(

read(input_path),

cond,

),

expr,

),

output_path

)While this approach looks perfect, the No-Free-Lunch theorem tells us that there should be some cons too. The first disadvantage is the complexity of implementation. I contributed once to the Apache Datafusion Comet project, and I can say that working with batches is much more mind-blowing compared to working with rows. To avoid losing parallelism and dropping to the Volcano-mode, you cannot just write a for loop and process the whole batch. You need to start thinking in terms of offsets and buffers instead!

While changing your approach to develop in a buffers-offsets-bitmask paradigm is possible, there are disadvantages that are difficult to bypass because they come from the limitations of SIMD itself. The most challenging case for SIMD is branching or multiple conditions. If you have an if-else in your vectorized operator, you can still benefit from computing both branches (if and else) since it will be much faster than iteration. However, what if you have multiple conditions? Or deeply nested conditions? For example, imagine you're working not with well-prepared Parquet or ORC files, but with raw heterogeneous JSONs that may have missing keys, different schemas, etc. In such cases, it's difficult to imagine an implementation that can truly benefit from SIMD and vectorization.

Another source of overhead comes from the bitmask. It should be obvious that with a bitmask and full-compute approach, an engine performs computations that aren't necessary. This works fine until the percentage of filtered-out rows exceeds 20-30%. Alternative approaches exist, such as selection vectors and non-full-recompute bitmasks. However, benchmarks show that different ratios of filtered-out rows require different approaches [5]. This forces you to either choose one approach and sacrifice performance in some cases, or implement multiple approaches. The latter option requires not only maintaining all implementations in your engine's code but also implementing adaptive query optimization that selects the right implementation based on the data. All these problems are compounded by the constant overhead of storing these masks or selections in memory.

Data-centric code generation and compilation

As I already mentioned, one of the main problems of Volcano-mode is the lack of benefits from modern CPU instructions and the chain of calls that can lead to runtime problems, such as garbage collection in JVM. How else can the engine work around this, except through vectorized execution? The answer is to generate new code from the chain of instructions and compile it. I think it's quite obvious that handwritten code made for a specific task and compiled for it will almost always be faster than any generic vectorized functions, especially when dealing with branching, which is the worst case for SIMD. How can this be achieved? Actually, the implementation is not so difficult. In the simplest case, it's just about adding string interpolation (simple formatted strings) to operators that have placeholders for variables that will be inserted at runtime. The second piece is a code generator that takes a sequence of operators, gets their f-strings, and combines them all together into code that will be compiled.

For our tiny case of the sequence ["read" -> "filter" -> "transform" -> "write"] it may looks like this:

class Operator(abc.ABC):

def do_codegen(self) -> str:

...

class Filter(Operator):

...

class Transform(Operator):

...

def write(input: Iterator[row], path) -> None:

...

def read(path) -> Iterator[BatchOfRows]:

...

def transform_with_codegen(

ops: Sequence[Operator],

input: Iterator[row],

) -> Iterator[row]:

code = ";\n".join([op.do_codegen() for op in ops])

native_function = compile(code)

for row in input:

yield native_function(row)

write(

transform_with_codegen(

[Filter(...), Transform(...)],

read(input_path),

),

output_path

)What can a compiler do here? Actually, a lot. A compiler can inline variables and even some results, significantly benefit from branch-prediction, reorder and rewrite code, etc. Most importantly, query engine can combine many operations into a single code-generation stage, so the compiler will provide us with code that is optimized not for "most cases" but specifically for the exact SQL query (or sequence of instructions in the form of a Logical Plan) that the user wrote! And of course the problem of multiple chained calls is not a problem anymore, because instead of function calls an engine will call compiled code for the whole stage once.

And, of course, there are downsides. While the initial development of code generation is very easy, maintaining and debugging it is hellish. Developers can no longer simply run a debugger and check where the problem is. Instead, they must manually intercept the generated code as well as input, transfer the code to an IDE, write a test with the intercepted input, and then run the debugger. Additionally, reading the code is very difficult for any end user of the query engine who wants to understand what happens under the hood. This occurs because there is no actual code in reality, only virtual operators with their own code generation. It worth to mention also, that dynamically generating and compiling code can introduce security risks (e.g., code injection) and stability concerns if not carefully managed.

Storage formats: row-oriented versus columnar

Unfortunately, only to understand the difference between physical execution, like vectorized versus compiled is not enough to answer the initial question about why Apache Spark is often considered as slow. So, let's briefly touch what kind of data can be an input for the query engine.

Row-oriented data

The canonical examples would be CSV or JSON Lines. A more advanced example would be Apache Avro. The core idea is that we are storing data as rows. The main benefits include constant complexity of append operations, so if you are building a write-heavy system, a row-oriented (or mixed) format can be a good choice.

Columnar data

The canonical examples are Apache Parquet and Apache ORC. The core idea is that data is stored as columns. Each column is, in simple terms, a continuous buffer containing all values of a specific column for all rows in a batch. The main advantage is that we can access a few columns for all rows, instead of reading all rows first and then dropping unneeded columns. This makes columnar formats a perfect choice for OLAP workloads where we often need to perform aggregations on most rows but only using a few columns. The main disadvantage is that adding a single row to the dataset requires reading all columns into memory, appending one value to each column, and writing everything back. This can be very expensive, even though in reality Parquet doesn't store entire columns but splits them into batches called row groups.

Structured versus semi-structured data

While Parquet is an obvious choice for well-structured data, handling semi-structured data may not be as straightforward. The challenge lies in semi-structured data having potential schema variations between rows. A canonical example would be heterogeneous dictionaries: maps (or JSONs) that have one generic umbrella schema, but each specific object may have missing keys, and the order of keys is not guaranteed. Such data can result from logs generated by different systems or from ingestion from NoSQL databases. While storing this type of data in JSON Lines format is straightforward, storing it in Parquet can be challenging because Parquet requires all rows (at least within a row group) to conform to the same schema.

Further reading

An article with comprehensive comparison of compiled and vectorized query engines [1].

Apache Spark

Apache Spark was initially designed as a distributed implementation of Volcano-mode through its RDD API. While the RDD API provides fantastic flexibility and quite good performance, it wasn't well suited for implementing SQL support. Therefore, in version 2.0, Spark introduced another API called SQL or DataFrame/Dataset API [6].

Catalyst Optimizer

The backbone of Spark SQL is the DataFrame API. While the Dataset (DataFrame) is just a raw Logical Plan from the user's input, Catalyst is a component that performs analysis and optimization.

Because a Logical Plan is just a sequence of operations and expressions (actually a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), but for simplicity it is enough to mention a sequence as a trivial case of DAG), it is worth checking what an expression is in Catalyst.

abstract class Expression extends TreeNode[Expression] {

...

/** Returns the result of evaluating this expression on a given input Row */

def eval(input: InternalRow = null): Any

...

/**

* Returns Java source code that can be compiled to evaluate this expression.

* The default behavior is to call the eval method of the expression. Concrete expression

* implementations should override this to do actual code generation.

*

* @param ctx a [[CodegenContext]]

* @param ev an [[ExprCode]] with unique terms.

* @return an [[ExprCode]] containing the Java source code to generate the given expression

*/

protected def doGenCode(ctx: CodegenContext, ev: ExprCode): ExprCode

/**

* Returns the [[DataType]] of the result of evaluating this expression. It is

* invalid to query the dataType of an unresolved expression (i.e., when `resolved` == false).

*/

def dataType: DataType

}It is an abstraction that contains many elements, including the following:

- The data type produced by this expression

- How to evaluate this expression on a single row (abstract method

eval) - How to generate the code for this expression (abstract method

doGenCode)

As one can already see, Spark's expressions can work in both Volcano-mode (via eval) and in the data-centric code generation mode (via doGenCode). While Volcano-mode support might seem redundant, just imagine how else User Defined Functions (UDFs) or simple user-created Expressions could work!

Catalyst Expression and codegen

Let's take a look at how code generation actually works. The simplest case among all expressions, from my point of view, are mathematical expressions. This is because most of them are built on top of a single abstract class that implements both doCodeGen and eval (actually it's nullSafeEval, but it's effectively the same Volcano-mode, except developers don't need to worry about nulls and can focus solely on the logic). The class itself has two main attributes: the function (f: Double => Double) and the name (name: String) of this function in the Java Standard Library (java.lang.Math). The nullSafeEval is simply a call to the function, while doGenCode is just an f-string that produces the full name of the function in Java's standard library.

abstract class UnaryMathExpression(val f: Double => Double, name: String)

extends UnaryExpression with ImplicitCastInputTypes with Serializable {

...

protected override def nullSafeEval(input: Any): Any = {

f(input.asInstanceOf[Double])

}

...

override def doGenCode(ctx: CodegenContext, ev: ExprCode): ExprCode = {

defineCodeGen(ctx, ev, c => s"java.lang.Math.${funcName}($c)")

}

}Most of the SQL unary math functions, for example, abs in Apache Spark are extending this abstract class. The same abstractions are present for Binary and other kinds of Expressions.

Fallback to the Volcano-mode

As I already mentioned, Spark can fall back to a chain of function calls (or to the Volcano-mode) and row-by-row processing if the expression implements a CodegenFallback trait. The most interesting part of this trait is the implementation of the doGenCode method. After carefully examining the code, one can realize that it allows not only falling back to iteration, but also incorporating Volcano-mode into the code generation! This is possible because doGenCode actually calls the eval method of the parent expression. Why is this important? Because in this case, Catalyst can combine expressions that support codegen with those that don't into a single code-generation stage. Even though the Java JIT compiler won't be able to optimize the eval code, it can optimize all other code as well as reduce the length of the chain (which, as I mentioned, can degrade performance and lead to expensive garbage collection inside the JVM).

/**

* A trait that can be used to provide a fallback mode for expression code generation.

*/

trait CodegenFallback extends Expression {

protected def doGenCode(ctx: CodegenContext, ev: ExprCode): ExprCode = {

// LeafNode does not need `input`

val input = if (this.isInstanceOf[LeafExpression]) "null" else ctx.INPUT_ROW

val idx = ctx.references.length

ctx.references += this

var childIndex = idx

this.foreach {

case n: Nondeterministic =>

// This might add the current expression twice, but it won't hurt.

ctx.references += n

childIndex += 1

ctx.addPartitionInitializationStatement(

s"""

|((Nondeterministic) references[$childIndex])

| .initialize(partitionIndex);

""".stripMargin)

case _ =>

}

val objectTerm = ctx.freshName("obj")

val placeHolder = ctx.registerComment(this.toString)

val javaType = CodeGenerator.javaType(this.dataType)

if (nullable) {

ev.copy(code = code"""

$placeHolder

Object $objectTerm = ((Expression) references[$idx]).eval($input);

boolean ${ev.isNull} = $objectTerm == null;

$javaType ${ev.value} = ${CodeGenerator.defaultValue(this.dataType)};

if (!${ev.isNull}) {

${ev.value} = (${CodeGenerator.boxedType(this.dataType)}) $objectTerm;

}""")

} else {

ev.copy(code = code"""

$placeHolder

Object $objectTerm = ((Expression) references[$idx]).eval($input);

$javaType ${ev.value} = (${CodeGenerator.boxedType(this.dataType)}) $objectTerm;

""", isNull = FalseLiteral)

}

}

}Vectorized execution

I already mentioned that Spark supports both Volcano-mode and data-centric code-generation. What about vectorized execution like in MonetDB/X100? Spark has this capability too, but only for specific cases, mostly related to processing data that is columnar by nature (Parquet, ORC, etc.). However, this same vectorization also works in any Apache Arrow related components, such as arrow-based UDFs and UDAFs.

The first abstraction for vectorization in Spark is a ColumnVector that contains a batch of rows. One thing worth mentioning is the isNullAt method that effectively functions like a bitmask or Selection Vectors in pure vectorized engines.

@Evolving

public abstract class ColumnVector implements AutoCloseable {

public abstract boolean isNullAt(int rowId);

}And the the second, a ColumnarBatch is the class that wraps multiple ColumnVectors into the batch. It provides a row view of this batch so that Spark can access the data row by row.

@DeveloperApi

public class ColumnarBatch implements AutoCloseable {

protected int numRows;

protected final ColumnVector[] columns;

...

}Unfortunately, at the moment only a small portion of all operations in Spark supports vectorization. So, even when working with naturally columnar data like Parquet or ORC, users will most likely see WholeStageCodeGen in the final physical plan rather than batch processing of columns.

Apache Spark execution model summary

Apache Spark (SQL) primarily operates with a row-oriented memory model and relies on code generation and JIT compilation of expressions, which are combined into stages by the Catalyst optimizer. At the same time, Spark supports fallback to Volcano-mode when necessary, such as when an expression like a UDF doesn't support codegen or when a DataType cannot be passed to the generator. Additionally, Spark has partial support for vectorized execution in the MonetDB/X100 style. Therefore, I would say that Apache Spark follows a hybrid approach.

NOTE: During job interviews in sections about Spark, it's common to hear a question about why UDFs, even Scala UDFs, are slow. The answer is already clear based on the information above: UDFs do not support code generation, forcing Spark to fall back to iterator mode.

The execution model of Spark is truly unified. It can effectively handle unstructured and semi-structured data while providing good enough performance on structured tabular data. At the same time, its code-generation approach allows Spark to function as a streaming engine too (FYI, the state-of-the-art streaming engine Apache Flink also relies on code-generation). The fallback mechanism in Spark makes it very easy to extend by writing your own expressions, which can be further optimized by implementing doGenCode if such expressions become bottlenecks in the overall pipeline.

Modern DWH: OLAP workloads on top of columnar data

While Spark is a truly unified query engine, it is often used as the backbone for Lakehouses: tabular data in cloud storage (or HDFS) with OLAP queries on top. Most cases when I hear the question "Why is Spark so slow?" are related to exactly this scenario. So, let's examine what the typical workloads in a Lakehouse are:

- Data is well-structured and stored in tables (Parquet files + metadata files + data catalog)

- All statistics about the data are pre-computed

- Data is mostly complete, with a large number of NULL values being rare

- Data is heterogeneous, with most tables being flat rather than nested

- Queries are purely OLAP: aggregations on columns, joins, and filters

- User-defined functions and code are used infrequently

- Conditions, especially nested conditions, are rarely used in queries

This is a perfect case for pure vectorized engines like Trino or Snowflake [7]. Aggressive vectorization, virtual function calls, and columnar representation of data in memory are exactly what you want for the described workloads!

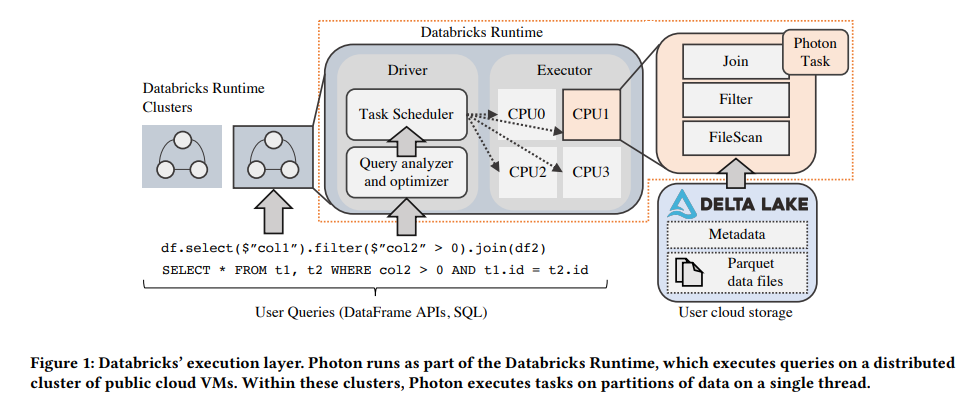

Turning Apache Spark into a pure vectorized query engine

I'm not reinventing the wheel here. All the things I mentioned are well known in the industry. For example, Databricks' engineers created the Photon extension for Catalyst with very similar motivation [8]. Databricks' Photon works as an extension for the Catalyst optimizer. It takes a final optimized plan and simply replaces the last step—the physical execution—switching from code-generation to vectorized execution based on virtual function calls.

In the very similar way works also open source extensions for the Catalyst: Apache Gluten (incubating) and Apache Datafusion Comet.

Conclusion

I very often hear that Apache Spark is slow. Is this a design or implementation problem with Spark? I don't think so. Spark is designed as a unified query engine, and it perfectly suits that role. You can process near real-time data via Spark Streaming, run ML workloads on top of Spark because of its excellent support for user code and rich API, process unstructured and semi-structured data, and perform complex transformations on data with excellent performance. You can also run OLAP workloads in the Lakehouse with performance that's not the best but good enough. Of course, if you don't need a unified engine, you simply shouldn't choose Apache Spark.

References

- Kersten, Timo, et al. "Everything you always wanted to know about compiled and vectorized queries but were afraid to ask." Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 11.13 (2018): 2209-2222.

- Graefe, Goetz, and William McKenna. The Volcano optimizer generator. University of Colorado, Boulder, Department of Computer Science, 1991.

- Boncz, Peter A., Marcin Zukowski, and Niels Nes. "MonetDB/X100: Hyper-Pipelining Query Execution." Cidr. Vol. 5. 2005.

- Neumann, Thomas. "Efficiently compiling efficient query plans for modern hardware." Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 4.9 (2011): 539-550.

- Ngom, Amadou, et al. "Filter representation in vectorized query execution." Proceedings of the 17th International Workshop on Data Management on New Hardware. 2021.

- Armbrust, Michael, et al. "Spark sql: Relational data processing in spark." Proceedings of the 2015 ACM SIGMOD international conference on management of data. 2015.

- Dageville, Benoit, et al. "The snowflake elastic data warehouse." Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Management of Data. 2016.

- Behm, Alexander, et al. "Photon: A fast query engine for lakehouse systems." Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Management of Data. 2022.